When might an Apple malware protection pose more user risk than none at all? When it certifies a trojan as safe even though it sticks out like a sore thumb and represents one of the biggest threats on the macOS platform.

The world received this object lesson over the weekend after Apple gave its imprimatur to the latest samples of “Shlayer,” the name given to a trojan that has been among the most—if not the most—prolific pieces of Mac malware for more than two years. The seal of approval came in the form of a notarization mechanism Apple introduced in macOS Mojave to, as Apple put it, “give users more confidence” that the app they install “has been checked by Apple for malicious components.”

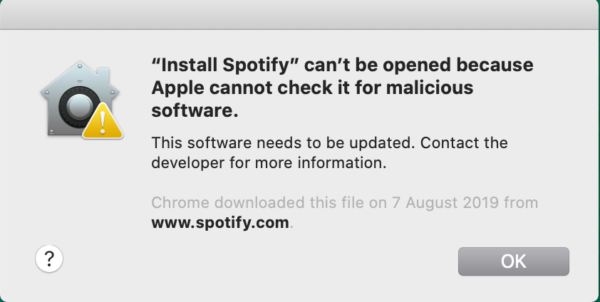

With the roll out of macOS Catalina, notarization became a requirement for all apps. Unless installed using methods not mentioned by Apple (more about that later), an unnotarized app will generate the following notice that says it “cant be opened because Apple cannot check it for malicious software.”

Classic Shlayer… with one big difference

On Friday, college student Peter H. Dantini found that homebrew[.]sh—a knockoff of the legitimate homebrew site brew.sh—was pushing a fake Adobe Flash update and warning users that their current version lacked the latest security updates.

It was a classic Shlayer campaign that was similar to hundreds or thousands of previous ones that also used fake Flash updates to infect users with adware except for one key difference: the trojan had been notarized by Apple. Patrick Wardle, who is a security researcher at the macOS and iOS enterprise management firm Jamf, said he believes this is the first malware to receive the notarization “stamp of approval.”

Wardle notified Apple on Friday of the erroneously notarized file, and the company quickly revoked the certification, a move that prevented the trojan from infecting up-to-date Macs. On Sunday, Wardle said, he found the site was serving new malicious payloads that were, once again, notarized by Apple.

“Unfortunately, a system that promises trust, yet fails to deliver, may ultimately put users at more risk,” Wardle wrote in a post. “How so? If Mac users buy into Apples claims, they are likely to fully trust any and all notarized software. This is extremely problematic as known malicious software (such as OSX.Shlayer) is already (trivially?) gaining such notarization!”

Antivirus provider Malwarebytes also weighed in, saying: “Unfortunately, its starting to look like notarization may be less security and more security theater.”

In defense of notarization

In a statement, Apple officials wrote: “Malicious software constantly changes, and Apples notarization system helps us keep malware off the Mac and allows us to respond quickly when its discovered. Upon learning of this adware, we revoked the identified variant, disabled the developer account, and revoked the associated certificates. We thank the researchers for their assistance in keeping our users safe.”

In Apples defense, the company has always been clear that the notarization is “an automated system that scans your software for malicious content, checks for code-signing issues, and returns the results to you quickly.” As such, Apple has never presented it as a comprehensive security check.

And even when notarization prevents an app from being installed normally, it's not that hard to work around the mechanism. As shown in the screenshot below, courtesy of Malwarebytes, unnotarized versions of Shlayer have long presented marks with a custom background that instructed them to right-click on a disk image file, rather than double-click it as normal, and then select opRead More – Source

[contf] [contfnew]

arstechnica

[contfnewc] [contfnewc]