Co-living in a pandemic: With Bay Area rent soaring, Mario Koran moved to Starcity, where kitchens and bathrooms are shared. Is socially distancing possible in a college dorm for grown-ups?

I’m living with 48 roommates in the middle of the coronavirus pandemic. Co-living makes physical distancing all but impossible: we touch the same door handles, awkwardly navigate shared spaces and binge-watch Tiger King in the same TV lounges.

The fear of coronavirus hasnt so far driven me to move out or reignite a grueling apartment search. But neither can I say with authority just how safe co-living is in the middle of an outbreak.

Before I moved to the San Francisco Bay Area in September, I was aware of the regions reputation for towering costs of living. But I wasnt prepared for the grinding hustle to find affordable housing. Even renting a room in someone elses apartment felt more like a job interview with prospective roommates.

I bounced between temporary rooms until I could find a more permanent place, living out of a suitcase, storing frozen meals in strangers refrigerators. At one point, I was willing to take a partitioned-off section of a living room someone was renting as a bedroom for $1,500. No dice: the tenants decided to “move in another direction” in terms of a roommate.

When I found Starcity – a tech-enabled real estate company thats part of a new generation of co-living spaces – it was, by all measures, an improvement to my living situation. It looks and feels a lot like a college dorm for grown-ups. The building is clean and well-lit, with a low-key, budget-trendy style. Beds and kitchen appliances are new. Showers dont inexplicably scald or give me frostbite. Laundry, soap and internet fees are included in rent. My room is my own space. The flexible lease was a major selling point and the price was right, too.

My apartment in Oakland rents for $1,250 a month – about $600 less than the median rent for a studio in Oakland and about $1,000 less than a typical one-bedroom.

This is how, at the age of 38, I effectively returned to my freshman year of college. I made a new group of pals and began to settle in. Then came the coronavirus.

Is it possible to protect yourself?

In spite of the pandemic, new residents continue to move into Starcity. But Ive also seen a good number of residents leaving with packed bags – some for good, others planning to wait out the worst of the pandemic with friends or family.

A couple of weeks ago, one woman sent me a message asking if I had any intel on penalties for breaking the lease. She couldnt do this co-living situation, she wrote, especially during Covid-19. Days later, she was gone.

Roshan Ramankutty, a software engineer in the sales department of Square who has become a friend, decided the best option for him is living with nearby family members.

“For me, it came down to: if the worst case scenario was to happen, how would I best be able to support and be supported? And thats ultimately with my family,” he said.

[contfnewc] FacebookTwitterPinterest[contfnewc]

[contfnewc] FacebookTwitterPinterest[contfnewc]Jon Dishotksy, Starcitys 36-year-old CEO and co-founder, says the company has received only a half-dozen lease cancellations since the lockdowns started. One Starcity staff member tested positive for Covid-19, he said, but so far there have been no known outbreaks in Starcity communities.

In a co-living environment, refrigerator handles, faucets and elevator buttons are all common touch-points. Even a trip to the kitchen to fetch a cup of coffee could put you in close proximity to your neighbors.

So is it actually possible to protect yourself from an outbreak in a place like Starcity?

Paula Cannon, professor of molecular microbiology and immunology at University of Southern Californias Keck School of Medicine, agrees that co-living certainly isnt ideal during a pandemic but says there are ways to minimize risk.

“If I was living there as a virologist, I would be your very annoying neighbor sticking leaflets under peoples doors that say heres what Starcity is doing and heres what we can do as neighbors,” she said.

Cannon suggests, for example, creating a schedule for the kitchen, so residents can space out meal times and reduce exposure to others. Cleaning and disinfecting the kitchen before and after each use would help. So would making your bedroom your castle and keeping to it as much as possible.

That, she says, requires residents to buy into a shared contract and agree to do their part to protect themselves and their neighbors.

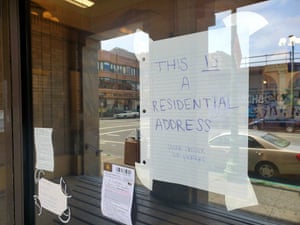

Health guidance aside, sheltering in place at Starcity hasnt always been convenient. Under lockdown, mail and packages to our building have stopped.

Dishotsky explains that receiving packages has been a challenge across Starcity communities, partly because they repurpose underused hotels or commercial spaces that lack places to store packages.

Weekdays see my neighbors waiting by its front door for deliveries for hours on end. Many packages have been rerouted, delayed, or stopped altogether. Hand-drawn notes decorate our front door, reminding delivery drivers: “THIS IS A RESIDENTIAL ADDRESS.”

[contfnewc] FacebookTwitterPinterest[contfnewc]

[contfnewc] FacebookTwitterPinterest[contfnewc]Its a small issue compared with the grim toll coronavirus has taken elsewhere. But its a valid concern at a time when deliveries remain one of the few ways for people to buy essentials.

So far, theres been no groundswell among residents to adopt a kitchen schedule like the one Cannon suggests, but that could change should someone in the building get sick.

While some residents have been keeping more to their rooms – emerging only occasionally, and with increasing edginess, to use the kitchen or shower – others see roommates as members of a traditional household and have given up trying to maintain six feet of separation.

Even Cannon recognizes that self-isolating at all times could defeat the fundamental benefit of group quarantine.

“Part of the draw of places like this is the sense of community, which helps people who have become near-suicidal because of isolation,” she says.

Indeed, having roommates has been instrumental in helping me beat back the madness that encroaches after days of solitude.

Weve passed time in childish and inane ways, spending nights eating Pringles and playing video games. We put on Pink Floyd albums and shot hoops at the downstairs basketball court until the wee hours of the morning. Suppertime sees a small troop of us rallying behind João, a Brazilian restaurant manager whos been laid off during the outbreak but continues to cook for those of us dug into the trenches of co-living alongside him.

And lockdown has shown me – as a hopeless introvert – how much Ive come to appreciate having, even need, others around.

The housing model of the future?

Dishotsky, who helped launch Starcity in 2016, grew up just south of San Francisco, in Silicon Valleys Palo Alto. His father, a Stanford professor, rented out rooms to students, rooting his son in co-living early on.

After a decade in commercial real estate, Dishotsky said he wanted to create something to help meet the Bay Areas most pressing need: a healthy stock of affordable housing options.

“I saw a way to make a dent in the housing supply and keep it affordable so a city doesnt push out its restaurant servers, postal workers, journalists – the ones who make up the backbone and underlying culture of our cities,” Dishotsky explains.

Over the years, Starcity has been featured in the New York Times, SF Curbed and CityLab, with stories exploring the degree to which a concept that once seemed absurd – a group of adults living together like college students – could be an answer to the lack of affordable housing.

Its also been subject to skepticism. In 2016 a local news outlet described Starcity as taking advantage of a loophole in city regulations that allows developers to buy single-room occupancy hotels, or SROs, flip them, then raise rents from, say, $450 to $2,100 a month at one San Francisco location.

“That was before we understood the full impact of converting SROs,” Dishotsky says of the criticism, adding that Starcity allowed previous residents at that address to continue to rent at the prices they paid before the building was renovated.

Since then, Dishotsky has been outspoken on the issue of displacement, writing in 2018 op-ed that he refuses to purchase or manage buildings that previously served low-income residents and calling on other developers to do the same.

[contfnewc] FacebookTwitterPinterest[contfnewc]

[contfnewc] FacebookTwitterPinterest[contfnewc]Dishotsky believes Starcitys model is resilient enough to outlast the pandemic, even as companies like WeWork, which offers shared office spaces, looks to scale back communal areas moving forward.

He sees co-living as a model of the future – one that will one day be embraced not just by single adults but whole families attracted to communal living and shared childcare.

As CEO, Dishotskys optimism isnt surprising. But Cannon, as a virologist, backs him up.

“I would be wary of attributing too much to how much coronavirus will change society. We have very short memories. Once we get a vaccine, and we will, people will re-emerge and things will go, mostly, back to normal,” Cannon says.

The silver lining, Cannon said, could be getting residents to embrace the social contract of taking precautions to look out for their neighbors health as well as their own.

“These things build trust and a sense of community,” she says. “Its the underlying human experiences that will ultimately get us through this moment.”

As for me, I dont plan to stay at Starcity forever. The lockdown will eventually pass and one day I might even find a place to settle down. Until then, Im leaning into the moment – even if that looks a lot like it did when I was when I was 19 years old.