Hawaii's Kilauea volcano, which has been spewing lava since May, gave a few key clues to scientists that an eruption might be imminent. Now, it looks like sound might prove to be another useful tool in the volcanologist's monitoring arsenal. By mapping out its unique "voiceprint," researchers could track any significant changes in activity deep within the volcano, per a recent paper in Geophysical Research Letters.

Volcanos make their own kind of music, typically emitting a lot of rumblings in the infrasound regime. These are low-frequency sound waves just below the range of human hearing, bottoming out around 20 Hz. By placing special microphones in the vicinity of a volcanic crater, it's possible to monitor the infrasonic sounds coming from within.

This is relevant to eruption prediction because those signals seem to get stronger just before a volcano blows, as with the 1998 eruption of Japan's Sakurajima volcano, or the 2015 eruption of Cotopaxi in Ecuador.

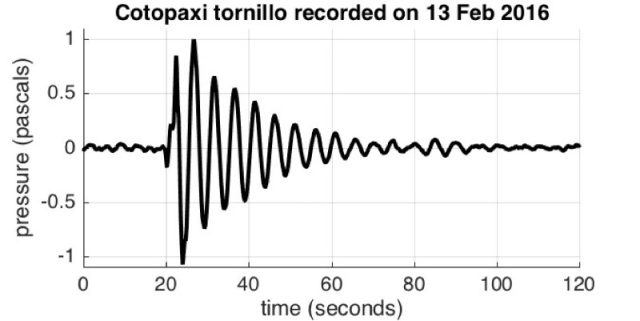

But it's not simply the strength of the sound that could predict eruptions, as the signals could be like an earthquake in the air. That's not just a fanciful analogy. Certain low-frequency earthquakes generate a screw-shaped seismogram dubbed a tornillo (Spanish for "screws"). When Cotopaxi erupted three years ago, a resulting explosion caused its crater floor to drop dramatically, changing its shape. Ecuadorian scientists who were monitoring its activity picked up a corresponding infrasonic signal on their instruments that reverberated for 90 seconds, oscillating back and forth in frequency as its intensity gradually faded into the background. The "voiceprint" of that signal is essentially a sonic tornillo. The volcano produced them about once a day for the first half of 2016.

Study co-author Jeff Johnson of Boise State University likens Cotopaxi to the "largest pipe organ you've ever come across." It has a deep narrow crater that forces volcanic gases to reverberate against its walls as they sweep through, much like a pipe organ makes sound from pressurized air moving through its pipes. The shift in the infrasound signal when Cotopaxi's crater changed its shape provided strong evidence that a crater's geometry determines the frequency and oscillations of that signal.

Every volcano should have a unique infrasound "voiceprint," according to Johnson, and once that voiceprint is known, any changes to the infrasonic signal would be an indication to volcanologists that something is changing deep inside the crater, possibly signifying an impending an eruption.

Scientists are also monitoring Kilauea with infrasound sensors, no doubt documenting how the signal has been changing over the course of this latest eruption. For instance, hot lava flowing down the mountain essentially drained the lava lake at its summit, so there should be a corresponding shift in the infrasonic signature. Precisely mapping how these shifts occur in relation to a crater's shape would be a boon to scientists hoping to predict the next volcanic eruption.

DOI: Geophysical Research Letters, 2018. 10.1029/2018GL077766 (About DOIs).

[contf] [contfnew]

Ars Technica

[contfnewc] [contfnewc]