Tom Gillespie, News Reporter

Eurovision Song Contest rules explicitly ban countries or performers from scoring political points.

Despite that, regular viewers have often seen the work of voting blocs and revenge plots unfold before their eyes.

Sky News take a look at the political history of the Eurovision Song Contest.

Standing up to Russia

The Ukraine banned Russia's performer from entering the country when they hosted Eurovision in 2017.

This likely enraged Kremlin officials who have earned a reputation for taking the contest rather seriously.

Ukraine's SBU security service banned Russia's entry Yulia Samoylova from country for three years after she had performed at a 2015 concert in Crimea.

Vladimir Putin's forces had annexed the region when Samoylova gave her performance.

This wasn't the Ukraine's first foray into Eurovision politics.

The Eastern European nation won the 2016 contest with Jamala's song 1944, which covered Joseph Stalin's enforced wartime deportation of the Tatar people to Central Asia.

The song narrowly pipped Russia's entry that year, inspiring Kremlin officials to claim there was an "information war" against their country.

Alexey Pushkov, head of the State Duma foreign affairs committee, wrote on Twitter that the contest had become "a field for political battles".

Ukraine won the contest for the first time in 2004 with Ruslana's song Wild Dances.

The performance was said to have helped Ukraine establish its post-Soviet national identity, with references to the Hutsuls people who inhabited the Carpathian mountains.

"Nul Points"

The UK has not won Eurovision for more than 20 years – and our last winning entry was Love Shine A Light by Katrina and the Waves all the way back in 1997.

Liverpool duo Jemini famously achieved "nul points" (no points) after their performance of Cry Baby in 2003.

The Eurovision humiliation was blamed, among other things, on the UK's involvement in the invasion of Iraq.

TV legend Terry Wogan, who provided the BBC's commentary on the night, famously said: "I think the UK is suffering from post-Iraq backlash."

Britain's participation in Eurovision 2018 will mark the second time it has competed since the vote to leave the European Union.

Many feared the UK was facing a 2003-style "nul points" snub after the Brexit referendum.

The nation breathed a sigh of relief when former X Factor contestant Lucie Jones finished in 15th place.

Some fans were anxious that the UK would no longer be able to participate in Eurovision after the referendum result.

But Alasdair Rendall, the president of the UK Eurovision fan club, has reassured fans that the UK's place is not under threat once the negotiations are over.

He said: "No, we would not be barred. All participating countries must be a member of the European Broadcasting Union.

"The EBU, which is totally independent of the EU, includes countries both inside and outside of the EU, and also includes countries such as Israel that are outside of Europe."

Rainbow nations

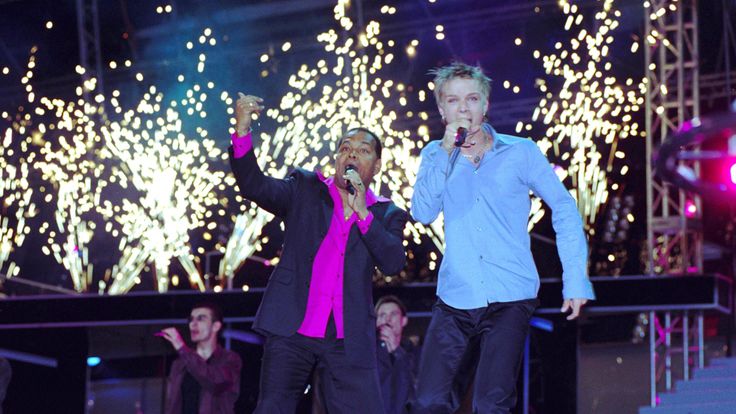

Flamboyant performers and elaborate props have helped shape Eurovision's reputation as the "Gay Olympics".

The performers' embracing of progressive and liberal ideas has rankled media outlets and radical groups across the world.

The first lesbian kiss took place in the competition in 2013, when Finnish entry Krista Siegfrids kissed a female dancer after her song Marry Me.

Turkish and Greek newspapers are said to have reacted negatively to the performance.

Austria's bearded drag queen Conchita Wurst won the competition in 2014, but only after radical groups from Russia, Belarus and Azerbaijan campaigned against her entry.

Mango TV, one of the China's most popular channels, blurred a rainbow flag that could be seen in the crowd during the first Eurovision semi-final in 2018.

Despite the occasional backlash, the contest has maintained its reputation for celebrating LGBT culture.

Same-sex couple traffic lights were erected in Vienna when Austria hosted the contest in 2015.

The lights showed loved-up red and green couples holding hands.

Bloc party

It's well documented that different "voting blocs" exist within the crop of Eurovision finalists each year.

Derek Gatherer, a lecturer at Lancaster University, has established a list of them which include the Viking Empire of Scandinavian countries and the Balkan Bloc made up of former Yugoslavian countries – as well as Romania, Serbia and Albania.

Mr Gatherer also cited The Pyrenean Axis which includes Andorra and Spain.

A surprise bloc is an apparent informal alliance between the UK, Ireland and Malta, which have consistently voted for each other over the years.

Eurovision expert Dr Paul Jordan explained: "Every year the UK depends on those seven or eight points from Ireland, to save us from the dreaded nul points."

He added that Greece and Cyprus have typically voted for each and not for Turkey.

Mr Jordan said the members of the Balkan bloc, typically one of the largest in the competition, tend to vote for each other for cultural reasons rather than loyalty.

He explained: "Bosnia and Serbia and don't really get on, and Albania and Serbia don't really get on, but they tend to vote for each other in Eurovision."

Although Russia failed to make it to the final in 2018, it has tended to do well in the competition thanks to its former Soviet satellite countries.

William Lee Adams, founder of the Eurovision-worshipping Wiwibloggs, said: "Everyone pays allegiance and homage to the mother Russia still.

"Russia could show up without a song and they could still make the final.

"It's not political, it's cultural.

"These people have a shared cultural heritage, so naturally there's going to be an affinity for the Russian song, which was probably made by Russian people."

Remembering genocide

Eurovision has a reputation for joyful and extravagant performances, but occasionally entrants strike a more sombre tone.

Armenia has twice used Eurovision to remind Europe of the mass killing of 1.5 million Armenians during the decline of the Ottoman Empire.

Many countries recognise the massacre as genocide, but Armenia's neighbours Turkey and Azerbaijan don't see it that way.

Armenian act Genealogy sent out a group of its natives from across five continents into the crowd for their song Face The Shadow in 2015.

They dealt with the same topic with their 2010 entry Apricot Stone.

Post-Soviet identity

Estonia became the first post-Soviet nation to win Eurovision in 2001.

Dr Paul Jordan, who wrote the book The Modern Fairy Tale: Nation Branding, National Identity And The Eurovision Song Contest In Estonia, said: "The Estonian case is an interesting example of the 'return to Europe' and the othering of the Soviet occupation.

"It was the opportunity for them to control their image for the first time since independence."

More from UK

Estonia's winning entry was "Nordic with a twist", with the country's prime minister telling crowds afterwards: "We freed ourselves from the Soviet Empire through song.

"Now we will sing our way into Europe."

[contf] [contfnew]

Sky News

[contfnewc] [contfnewc]