In 1982, a computer scientist named Scott Fahlman was chatting on an online bulletin board, and used a combination of a colon, a hyphen and a round bracket to indicate that he was joking. This was likely the first emoticon, a kind of emotional shorthand that emerged in online communications to compensate for the loss of in-person tonal clues (facial expressions, gestures, and so forth). Then came emoji, which started spreading rapidly into wider use around 2011. Emoji are now used by roughly 90% of the online population.

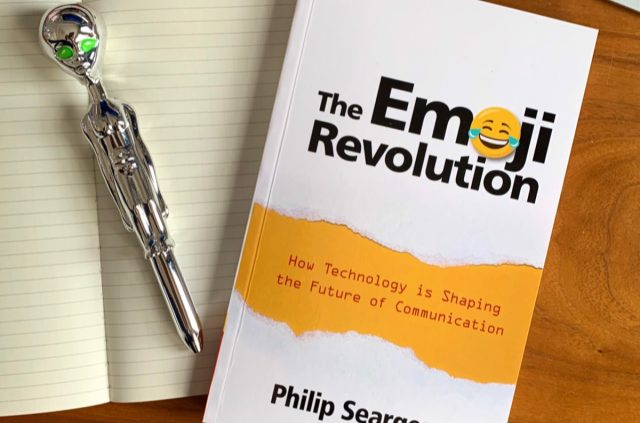

That makes them a keen topic of interest to linguists like Philip Seargeant. Seargeant is a senior lecturer in applied linguistics at The Open University in England. His specialty is the study of language and social media, with a particular focus on the politics of online interaction. Given his linguistics expertise, he naturally found himself intrigued by the rise and eventual dominance of emoji in online communication, and that fascination led to his first popular science book: The Emoji Revolution: How Technology is Shaping the Future of Communication.

"I've always been interested in a mixture of the visual as a sort of language," Seargeant told Ars. "Emoji are often seen as very frivolous, a little bit childlike. But at the same time there's something more serious about the way they're being used, despite their cartoonish look—both in the way people use them, and in the sophistication they have as language."

A rich history

The emergence of emoticons and emoji has been driven by rapid technological changes as the Internet became a dominant force for global mass communication. It's brought along with it the usual handwringing from change-averse elders about how their usage is destroying language. But far from being a unique feature of the Internet era, Seargeant argues that human beings have long sought to find these kinds of visual shortcuts to indicate tone.

For instance, John Wilkins, a co-founder of the Royal Society in the 17th century, believed that the limitations of language were holding back scientific progress. He dreamed of inventing a universal language, and went so far as to construct a group of symbols with several colleagues he called "Real Characters." These were not written representations of spoken words; rather, they represented key concepts visually, much like emoji do today. In the 1580s, an English printer named Henry Denham proposed the use of a reversed question mark to indicate irony. The late 19th century writer Ambrose Bierce, author of The Devil's Dictionary, proposed implementing a "snigger point," which he argued should "be appended … to every jocular or ironical sentence." Clearly, there has long been a need for symbols to augment written language.

Ars: I found the early history of failed attempts to augment written communication with symbols fascinating. Yet none of these earlier attempts really took hold on quite the same level as emoji. Is that because of today's rapid technological changes?

Seargeant: You can think of writing itself as a type of technology, in a way that speech isn't. Speech is something that we all naturally do as we grow up. The alphabet is a technology. Writing was invented. In that sense, emoji are just part of that history, part of the human condition. On the other hand, it's very specifically a part of that history as it relates to digital communication devices. Emoji is very much suited to what we do on social media now. The main advantage is that it adds emotional coloring, or emotional flavor, to written language. Written language can obviously express things in great nuance. But when you're writing on social media quickly, in a conversational style, a lot of that stuff gets lost. Emoji are a way of adding that back in.

It's very difficult to invent a language and then assume people will pick up on that. It's sort of organic. It's being in the right place at the right time, being backed by the right people at the right time. When Apple added emoji to the iPhone, that gave it a huge boost. This is why its rise is tightly linked to corporate history and corporate culture. But the creativity part of it is another reason why they're so popular. You can do quite innovative things in a very simple way with things like Bitmoji or Memoji. You can design them to look like yourself.

Ars: What about all the grumpy curmudgeons writing OpEds about how text-speak and emoji used by kids today are "ruining language"?

Seargeant: There's a natural tendency for people to have these sorts of mini moral panics. It's not just emoji, before it was texting, before that it was probably something else, even back to people sending telegrams. So it's very much generational, like teen slang. Young people are doing things in ways that other people disagree with, and so they see it as degenerate. But language always changes; patterns of language shift constantly. It's incredibly complex. We all have a repertoire. Emoji is just another instance of a new repertoire coming along.

"You have to have a sophisticated understanding of how language and communication work to use emoji."

There's also this complaint that it's ruined literacy among young people, because they're just sending emoji. Again, that's not the case. You have to have a sophisticated understanding of how language and communication work to use emoji—like using them in a playful way, building words from putting two emoji together, and so forth.

That saiRead More – Source