I'm not shocked that the first-ever Minecraft board game is cute and fun. But this new game, made as a collaboration between video game studio Mojang and board game producer Ravensburger, has no right to be this elegant.

Minecraft: Builders & Biomes is breezy. It's quick. It's kid-friendly. Yet it's full of the tricky decisions, competitive countermeasures, and three-moves-ahead plotting that can ratchet a game to the top of a diehard tabletop community's rankings.

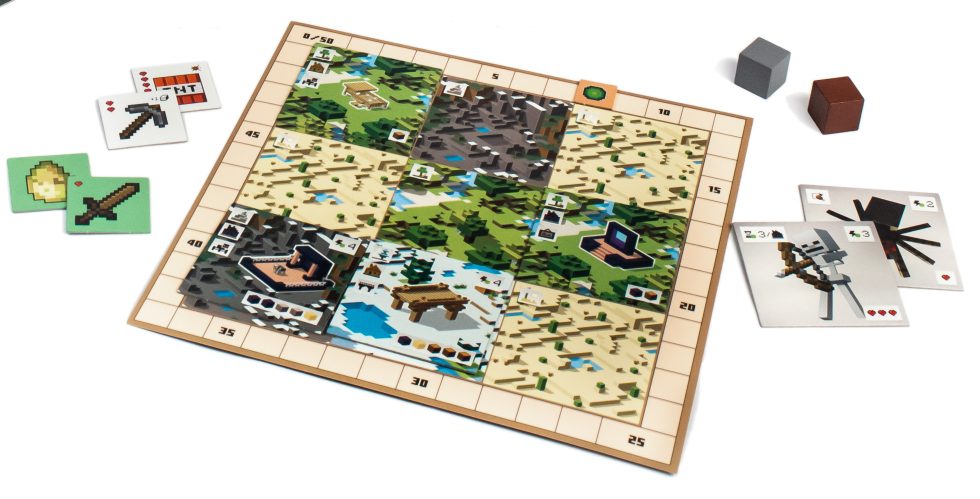

Best of all, it has a goofy, tactile centerpiece that feeds into the gameplay loop while also looking exactly like what you'd expect from a "Minecraft board game." Builders & Biomes, which is out now in Europe and launches in the US on November 15, has come out of nowhere to punch my licensed-game skepticism down like a blocky, in-game tree.

Minecraft meets Jenga?

A more accurate name might have been "Minecraft: Builders & Battlers." The object is to rack up experience points before a game-over condition is triggered, and you can do this in one of two ways: build structures or kill monsters ("mobs"). Yes, that sounds generic, and I'll get to how those objectives run in parallel.

But any conversation about M:B&B should begin with its clever twist on resource gathering: the "block base."

Here's the fancy, official photo of the block base. Here's how it looks in real life. The blocks do stay quite stable, even as players take the blocks off one at a time through the course of play. You'll eventually grab tiles off the primary board, but in order to do so, you have to cash in the blocks you've picked up. Notice the bottom-right icons on the bottom-right tile? These are the tile's cost in blocks. The other icons refer to what type of biome, material, and building type each tile has, which counts toward the scoring phases.

The game includes 64 chunky wooden blocks split into five colors: yellow (sand), brown (wood), gray (iron), black (obsidian), and green ("wild"). Dump these blocks into a cardboard sleeve until they fit together evenly, then lift the sleeve up. Presto: You now have a block base, four tall by four wide by four deep, and you will spend each session picking it apart with your hands.

In Minecraft tradition, you need to "mine" these blocks to build anything, but you can't take a block unless it has at least three sides exposed. At the outset, that means you can only grab blocks from the top layer, and only those on its outer edge. Eventually, as more blocks are pulled away from various angles, certain blocks wedged into the middle of the structure might have three sides exposed.

You'll want to frequently spin the block base around via an included cardboard sheet in order to see which blocks might have inadvertently opened up. Plus, be careful about which blocks you take, because with each block you remove, another block—perhaps the exact one your opponent wants—could open up with your choice out of the way.

In one more cool twist, the game's scoring phases revolve around the block base's four layers. On your turn, you can grab blocks from whatever layer you want (so long as the "three sides exposed" rule applies). The instant the entire top layer has been removed, one of the game's scoring moments is triggered. The same goes for when the second and third layers have been completely whittled down; the third layer's completion is, in fact, the game-over condition. This sometimes creates a quandary: do you rush into removing a layer's blocks even if you're not ready to score points and even if those blocks are useless in your building plans, just to stop other players from racking up a higher score?

Pardon my gushing, but I cannot get over how lovely the block base works in action. Its mix of spatial examination and tactile resource gathering is not just cool as a board game mechanic, but also completely on brand for the Minecraft universe. Bravo to whoever put this board gaming masterstroke together.

A family-friendly game with tough tactical decisions

A sample three-player game. The tiles in the middle represent a shared gameplay board, on which players move their own hero figurines. The three other sheets are each player's personal biome grid, on which they build and place new structures in order to rack up points in the game's three scoring phases. Ravensburger The shared tile board at a game's outset. Players move between the tiles, not on top of them, and this lets them potentially access or take any of four pieces at a time, should they stand at an intersection. Sam Machkovech As you move around the board, you'll expose the tiles. Buy the building tiles with the wooden blocks you've accumulated. Battle the mobs with any weapons you've accumulated (including the chests on the board's edges, which require more movement to reach and pick up). Sam Machkovech The game includes three scoring phases. At each of these, if you have contiguous, matching tiles on your personal board that match these cards' icons, you'll score more points. Sam Machkovech

That clever system is the centerpiece to an otherwise familiar resource-gathering game, albeit one where players can only perform two actions on a given turn: take two blocks from the block base, move your hero piece up to two spaces, build, fight a mob, or collect a weapon card. And you cannot perform any of those actions twice in a turn (meaning that you can't grab four blocks and end your turn), so there's a tension to the choices you make and what you may leave available to opponents as they follow in clockwise order.

When you move your hero piece around the board, this also lets you flip over any board tiles adjacent to your hero. Tiles can either be buildings (which you can take off the board and "build" on your personal player board by spending whatever required blocks are listed on that tile) or mobs (which you can battle using the game's combat system).

It's not as simple as collecting blocks, walking up to building tiles, and spending the required resources. You're also trying to build a perfect grid on your player board with each scoring round in mind. Each building tile has three icons: one for its biome, one for its materials, and one for its building type. Each of those icons corresponds to one of the game's scoring rounds. When the first scoring phase is triggered, you'll want to have as many matching biome squares on your board as possible, and they only count as a combined scoring group if they're all touching horizontally or vertically (not diagonally). You only get to score one type of biome, not two, so you'll have to pick your highest-scoring option.

Each player board comes with a bunch of biomes by default, so you can conceivably build only one or two buildings to connect matching biomes (desert, forest, mountain, or snow). But certain biomes are worth more than others, and the more valuable ones require trickier build patterns. You'll have to cover existing biomes with new ones to, say, chain together the snow biome in an all-squares-touching pattern. And, of course, opponents can keep an eye on what you're plotting as they too move around the board, pick up the block base's resources, and snRead More – Source