SANTA MONICA, Calif.—The Ukrainian game developers at 4A Games don't hesitate to list Half-Life 2 as a defining inspiration for Metro, their long-running first-person shooter series. A 4A representative at a pre-E3 event in May cited Valve's linear storytelling and knack for cinematic presentation as defining tentpoles for the games Metro 2033 and Metro: Last Light, which the studio now calls "two halves of the same game."

So what, then, has driven inspiration and development on next year's sequel Metro Exodus? 4A isn't specific. Instead, it vaguely refers to modern gaming as "the era of the best single-player games in years." That's its competition, the studio says.

But after two hours playing through the massive, harrowing, open-world terror of Metro Exodus, it's hard to escape the feeling that 4A had a specific goal in making a new, epic game with the word "Metro" on the title: not to beat an existing game, but to make the open-world version of Half-Life that Valve never got around to slapping the number "3" onto.

Redefining the point of open-world games

That's not to say the Metro Exodus demo I played was a remarkable take on Valve cornerstones like experimental weapon design or first-person narrative framing. Rather, 4A has applied its brutal style of difficult combat to something gorgeous and harrowing—and in doing so, may have turned the concept of open-world quest design on its head.

4A describes Exodus's design as a mix of open-world and linear. Its players will explore one open-ended hub world at a time before completing a linear mission that connects to the next open-ended hub space. Each open zone's map only has its primary missions marked, either by icons on a mini-map or by NPCs yelling for you to follow in their direction. But Exodus quickly makes apparent why a player would—or would not—want to skip the beaten path.

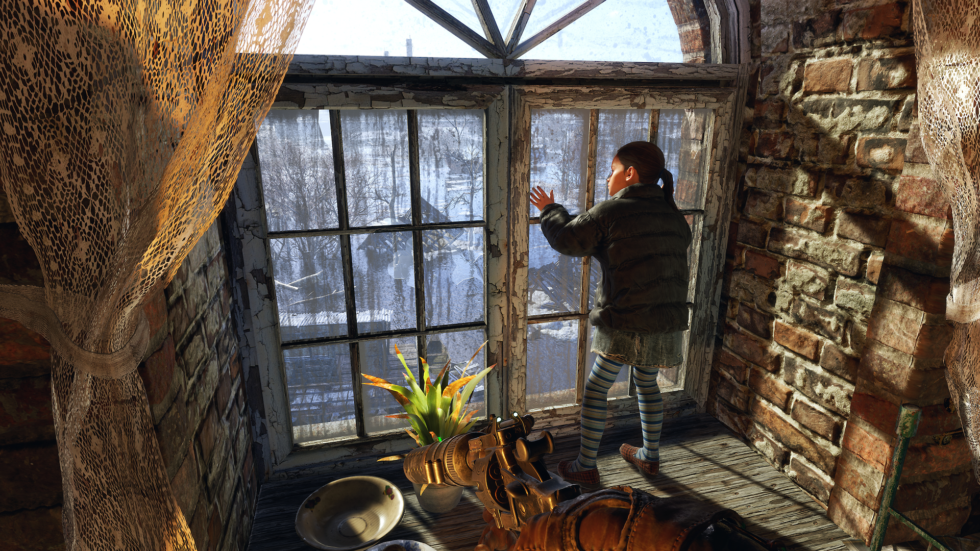

Metro Exodus begins with you stepping off this derailed train and figuring out your next steps. Your wussier comrades decide to hang out by the train, even though it was shot at by locals. Smart move, idiots. To be fair, though, a few steps in the wrong direction from the train will lead to a deadly encounter with this flying demonic… thing.

"We don't have arbitrary side missions or busywork for players to do," Deep Silver brand manager Huw Beynon says. "Every hut, church, and town has a story to tell, a narrative purpose in the game. You'll always have a clear story objective to find, but open environments give you the freedom to explore the wider world, woven organically into the narrative. We want to give players free agency without giving up the urgency of storyline."

What Beynon misses in that description is crucial. Metro Exodus has a clear philosophy about side quests: they are equal parts must-do and must-avoid.

I quickly learned what not to do when I skipped away to the south, after my opening-game companion Anna asked me to follow her to the north once we'd disembarked from a freshly derailed train. When I disobeyed her command, she shouted a firm-but-understanding retort about my sway to stray. Almost immediately, I was hounded by a four-strong pack of mutant wolves; a trio of human frontiersman; and a nuclear pterodactyl. I almost immediately burnt through all of my ammo, health, and resources. I rebooted the demo, admitting defeat to Exodus's brutality. Time to try again.

This time, I followed Anna, and this path was generally kinder, but it quickly got weird. I found myself at a converted church, cut in half by a river, and its welcoming hosts turned dark. This was an anti-technology cult, I soon learned, and as its denizens' greeting became increasingly hostile, I diverted my path—and ran into one cult member who asked to be saved. (Her flag-waving in the distance was what had even drawn Anna and me to the spot.) I helped get her out, but I had an option on the way out: skip away immediately, or hang around and take out the freaks.

Doing this unearthed equal parts loot, bullets, and story, with the cult's creepy shades of gray becoming apparent as I found its non-soldier denizens hiding in various quarters. One resident, in particular, accused me of being a "Satanist"—and then almost immediately demanded I take him with me. (I had no button-prompt option to aid him on his dark endeavors, sadly.)

One blind, decrepit woman who I found hiding in a small room mumbled in depressing fashion for a bit. I shot her in the head, thinking I'd be doing her a favor. The game didn't appreciate my sociopathic take on "empathy," however. It registered this kill as a "negative," which I hadn't triggered before since I had merely knocked the church's defenders unconscious while gathering loot. I was told on my way out that this murder would bear consequences.

In spite of my sociopathic fumble, this was the most shining example of "how deep do you want to go" in terms of Exodus's handling of "side" missions and their related stories. I could have run away and made sure I didn't burn through any more precious supplies, or I could take my time, dig through carefully, and potentially unearth some desperately needed health and ammo—all while flipping through figurative pages of Exodus's world-building bible.

Quite frankly, I hate when open-world games revolve around map icons and beacons to predictable, fetch-driven side quests. I prefer the approach evidenced by the first two hours of Metro Exodus: take any interesting-looking sidetracks as you march through the primary campaign, whether they're in your immediate vicinity or hugely visible on the horizon, and chances are, something that's interesting, relevant, or compelling will be packed in there. And thanks to brutal difficulty, Exodus organically drives its players to fake like a careful, curious packrat, instead of following an on-screen compass.

Will combat be good enough?

But Exodus, at least in its preview state, still struggles to walk the tightrope between meaningful challenge and unfair insanity. I consistently found myself sticking to safe and stealthy paths, avoiding conflict and gathering resources, only to find I was getting absolutely mauled and burning through my every resource all too quickly. In one sewer level, overrun with humanoid post-nuclear monsters, I was out of ammo and stuck. Rather than reload a milder save file, I found myself having to run until I tricked baddies to march at me in a straight line so that I could spam a melee attack over and over and over until they all died.

Which is a shame, because when I was playing sloppily on purpose and chewing through bullets, I found the beasts were a terrifying delight to face, with multiple creatures swarming in a pack-mentality way while dodging and weaving with great menace. I appreciate the way that Exodus opens with ammo scarcity and resource management as a priority, and I'm hopeful that 4A fine-tunes the balance between increased power, increased challenge, and non-spammy survival options over the course of hopping between its open hub zones. (We're hopeful that Exodus' new reliance on crafting and discovering new weapon and upgrade blueprints around the game world will be breadcrumbed well enough to maintain the game's power-up momentum.)

Even in its early state, Exodus is an absolute visual stunner. The studio's updated 4A engine is a marvel to behold, mostly because of its ability to crank out impressive view distances bathed in dynamic lighting effects that gleam from within and without. We got a hint at the game's mix of a time-of-day system and evolving seasonal effects, as we watched day approach night during our demo's timespan and got caught up in a brutal, particle-filled thunderstorm.

The written dialogue likely won't be as impressive, as thick Eastern European accents bang their way through an awkward, overly direct script in the game's opening portion. That's one loud reason why my bold Half-Life 3 reference might ring hollow to anybody following Metro Exodus closely. But 4A's combination of visual polish, intense monster combat, and inventive quest breadcrumbing, even in this incomplete state, really do feel like the stuff of Valve devotees wanting to make the open-world genre a little more Gordon Freeman-y. We'll have to wait until "Q1 2019" to see if the efforts have truly paid off on Windows PC, Xbox One, and PlayStation 4.

[contf] [contfnew]

Ars Technica

[contfnewc] [contfnewc]