Tucked into an economic development bill signed by Massachusetts Gov. Charlie Baker earlier this month was a little-noticed provision that could have a big economic impact for Massachusetts workers. The language, introduced by state Rep. Lori Ehrlich, aims to rein in the abuse of employee noncompetition agreements in the state.

In a Thursday phone interview, Ehrlich told Ars that her work was motivated by hearing from hundreds of Massachusetts workers who had suffered from the abuse of noncompete laws. In one infamous case, a summer camp got a high school student to sign a noncompete agreement that effectively barred her from working at another summer camp the following year.

"We heard from people working at pizza parlors, yogurt shops, hairdressers, and people making sandwiches," Ehrlich said. "Those stories were incredibly compelling and really drove the narrative for change."

The legislation Baker signed this month prevents these kinds of abuses by banning the enforcement of noncompete agreements against minors, students, and low-wage workers generally. It also introduces important procedural protections, guaranteeing employees notice and an opportunity to consult with an attorney before signing noncompete deals.

The Massachusetts legislation also has symbolic importance because Massachusetts plays a central role in the most famous case study of the economic consequences of noncompete enforcement. California courts refuse to enforce noncompete agreements at all, and some scholars argue that this difference was a key reason Silicon Valley pulled ahead of Boston in the 1990s to become the nation's high-tech capital.

But ultimately, lawmakers decided not to adopt California's approach. So while the Massachusetts bill took a number of steps to crack down on the abuse of noncompete agreements, it left Massachusetts workers with weaker protections than workers enjoy in California.

"The legislature made the determination that noncompetes do serve legitimate business purposes and shouldn't be prohibited," said Russell Beck, an attorney who helped draft the legislation.

Did noncompetes destroy the Massachusetts Miracle?

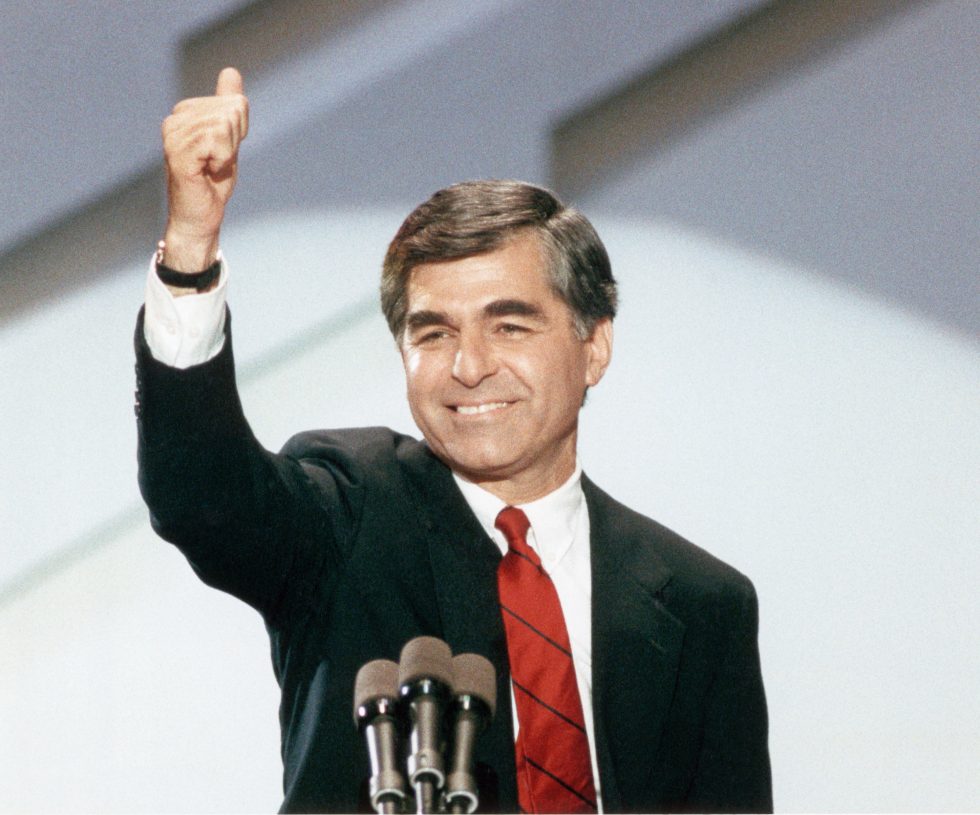

Today, Silicon Valley is universally recognized as the high-tech capital of the United States. But until the 1980s, Boston's Route 128 corridor could have made a credible claim to that title. Boston was the center of the minicomputer revolution of the 1970s, and by the 1980s companies like Digital Equipment Corporation, Wang Laboratories, Data General, and Prime Computer provided tens of thousands of jobs in the Boston metropolitan area. Massachusetts governor Michael Dukakis touted this "Massachusetts Miracle" during his 1988 presidential campaign.

But the Route 128 corridor struggled in the 1990s. Those minicomputer giants mostly failed to adapt to the PC and Internet revolutions, and the region wasn't able to nurture a new crop of technology giants to take their place. Boston is still an important technology center, of course, but today it lags far behind Silicon Valley.

Why did Boston fail to keep up with Silicon Valley? In an influential 1994 book, political scientist AnnaLee Saxenian argued that Silicon Valley had a uniquely free-wheeling engineering culture, with employees job-hopping from one company to another, taking their technical skills with them. This culture allows Silicon Valley companies to adapt quickly to technological change. It also makes it common for people to leave secure employment at an established technology company to start a new firm—often one that competed with the old employer.

A few years later, legal scholar Ronald Gilson pointed out one of the major factors driving this culture: California courts consistently refuse to enforce noncompete agreements. In most states, including Massachusetts, high-tech employers can, and frequently do, ask employees to sign agreements limiting their ability to move to a competitor or start a competing company. But such agreements can't be enforced in Silicon Valley.

Of course, any particular company would prefer to have the ability to lock their own employees in with these kinds of restrictions. But it's also easy to see why nixing these kinds of agreements would be beneficial for a region like Silicon Valley.

"Employee mobility spreads knowledge of new technology around," says James Bessen, an economist at Boston University. "More people can learn and adopt the technology." Employee mobility also gives workers a greater incentive to improve their skills, Bessen told Ars, because employers that don't pay competitive rates for an employee's skills will lose them to someone who does.

Often individual employees at large technology companies have good product ideas, but struggle to convince their company bureaucracies to implement them effectively. In California, such an employee has the option to take a job at another company—or start a new one—to pursue the idea. In a state that strictly enforces noncompete agreements, in contrast, job-switching might not be a practical option, causing the idea to wither on the vine.

This could explain why Silicon Valley has been able to jump from one wave of innovation to the next. Silicon Valley began as a center for computer chipmaking—hence the name—but over time it became the home of leading technology companies working on personal computer hardware and software, Internet services, mobile devices and apps, and so forth. Disruptive innovations have caused the death of many individual Silicon Valley companies, but the region as a whole has thrived, as talented employees at declining companies could easily switch to up-and-coming firms.

"Allowing workers to move to jobs that better suit their preferences and talents is important both for them and the broader economy," says Ryan Nunn, an economist at the Brookings Institute.

The idea that California's worker-friendly laws contributed to Silicon Valley's dynamism makes some intuitive sense, but it's a difficult theory to test empirically. Any number of factors could have contributed to Silicon Valley's success and Boston's relative decline as a high-tech center. Meanwhile, states with stricter noncompete enforcement, including Washington state, have nurtured thriving high-tech economies of their own in recent decades.

Still, state policymakers have to wonder whether noncompete laws could be holding back innovation in their states. In 2015, Hawaii passed legislation adopting a California-like approach to noncompetes—but only for technology companies. Hawaii not only bans enforcement of noncompetes by software firms, it also voided non-solicit clauses preventing technology workers from recruiting former colleagues to work at their new employer.

The Massachusetts legislature rejected broader reforms

Legislators in Massachusetts have been considering proposals to reform noncompete law for almost a decade. In early 2009, around the same time Rep. Ehrlich introduced her original reform bill, another Massachusetts legislator, then-Rep. Will Brownsberger (now a state senator) introduced legislation for a California-style ban on noncompete agreements. Ehrlich tells Ars that she and Sen. Brownsberger became interested in the issue independently but quickly started to work together.

The proposals attracted ferocious opposition from established business interests in Massachusetts. Multiple sources told us that EMC—a Boston-area IT giant that became a subsidiary of Dell in 2015—was a major force opposing early reform proposals. Established industry groups, including the Associated Industries of Massachusetts, argued that noncompete enforcement was essential for Massachusetts businesses.

The obvious counterpoint is that there are plenty of successful businesses in California—so noncompete enforcement can't be that important. I raised this point with Russell Beck, a Massachusetts lawyer who drafted some of the noncompete language that became law last week.

"California has by far the most trade secrets litigation," Beck pointed out to me. "The inference I draw from that is that companies need to protect their information one way or another, if they can't use noncompetes, they're going to use trade secrets law."

Ultimately, opponents of sweeping California-style reform had enough votes to block legislation adopting a California-style ban on noncompete enforcement. So negotiations focused on Ehrlich's own less sweeping—but still quite significant—bill to rein in abuse of noncompete clauses.

[contf] [contfnew]

Ars Technica

[contfnewc] [contfnewc]