As the coronavirus spread rapidly around the world, and more people became aware of the serious threat it posed, the 2011 film Contagion experienced a sudden resurgence in popularity. The Steven Soderbergh-directed thriller moved from 270th place pre-pandemic on the most-watched list of Warner Bros. movies to second place in just a few months. The biggest spike in Google searches occurred on March 11, the same day President Trump announced a travel ban on Europe, peaking again three days later, when the ban was extended to the United Kingdom.

This struck Coltan Scrivner, a graduate student at the University of Chicago specializing in the study of morbid curiosity, as remarkable, especially when he noted a similar spike in popularity for the 1995 film Outbreak. Why would people seek out the very kinds of films and TV shows that someone feeling threatened by a pandemic might be expected to avoid? He conducted an online survey to learn more. The result is a forthcoming article in the journal Evolutionary Studies in Imaginative Culture.

Scrivner's hypothesis is that such "morbidly curious" behavior is an evolved response mechanism for dealing with threats by learning from imagined experiences. "We might reason that these search terms spiked in popularity because people were trying to learn more about the coronavirus outbreak in response to its recent impact on their daily life around that time," he wrote in his paper. "The shutting of international borders may have signaled to the American consciousness that the coronavirus was, in fact, a real threat." And part of the human impulse to prepare for said threat would be to learn more about it—including seeking out fictional representations of said threat.

His hypothesis is similar to the work of Mathias Clasen of Aarhus University in Denmark, author of Why Horror Seduces, who specializes in studying our response to horror in books, film, video games, and other forms of entertainment. Clasen's core hypothesis is that horror exploits the evolved fear system. In other words, we seek out being afraid in controlled settings as a means of confronting our fears in a safe environment. It helps us challenge our limits, practice coping mechanisms, and learn how to better regulate our fear. The same could be true for the sudden spike in interest in pandemic-related entertainment.

One of the first things Scrivner did when he began studying morbid curiosity was to come up with a validated scale by which to make assessments. He found that most people cluster into four types of morbid curiosity: violence, supernatural dangers, body horrors (such as a pandemic), and the minds and motives of dangerous people, characteristic of the true crime genre. So Scrivner already had a valid metric on hand when he had the idea to conduct an online survey examining how the current coronavirus-driven pandemic was influencing people's choices in film and TV programs.

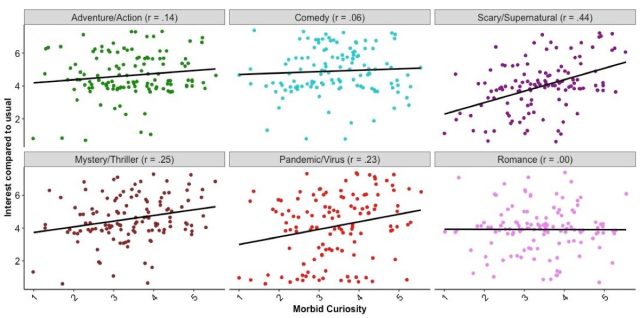

Scrivner recruited 126 participants to complete his Morbid Curiosity scale and then answer questions about how interested they were in the coronavirus, and their current level of interest, compared to normal, in six different film and TV genres: scary/supernatural, mystery/thriller, pandemic/virus, romance, action/adventure, and comedy. He found that those who ranked higher on the morbid curiosity scale tended to seek out not just pandemic movies during this current outbreak, but also films and TV shows in the scary/supernatural and mystery/thriller categories.

This was just a quick initial study, and Scrivner plans to refine his approach in the coming months, collaborating with Clasen, among others. In the meantime, we asked Scrivner to provide a list of ten recommended pandemic-related films—some obvious choices, some less so—for Ars readers who feel inclined to indulge their morbid curiosity. They're presented below, divided into five sub-groups with two representative films in each: pandemic, lab accident/zombies, quarantine, fear of the outdoors, and comic relief.

(Mostly mild spoilers below.)

Pandemic

This is an obvious choice, since it inspired Scrivner's study in the first place. The real-world parallels are striking. Contagion deals with a fictional respiratory virus (originating in China) similar to the flu—but more contagious and much more deadly. It spreads rapidly through city after city, leading to widespread government quarantines and, eventually, a breakdown of social norms as people succumb to fear and hysteria and resort to looting and violence. It has been praised for its remarkable scientific accuracy, both in its depiction of the virus and how it spreads and in the race to develop an effective vaccine. (Granted, they discover the vaccine far more quickly than usually happens in the real world. Chalk it up to "Hollywood time.")

Outbreak deals with the re-emergence of a deadly virus called Motaba, 28 years after it first appeared in an African jungle, infecting US soldiers. The US military destroyed the camp to conceal evidence of the virus, and when it re-emerges in Zaire, a series of bad human decisions—from stubborn denial that it could spread, to crass opportunism—cause it to spread. The deadliest outbreak hits the fictional town of Cedar Creek, California. The military declares martial law in the town as scientists race to develop a cure, even as a nefarious major-general plots to develop the virus as a biological weapon.

From Scrivner's perspective, both of these films provide a way to explore how humans actually behave during a global pandemic. "How are people quarantining themselves? What are governments doing?" he said. He admits to being "shocked" at how well Contagion in particular portrayed "how people would freak out, and how they would buy into these miracle cures," as well as the spread of misinformation and conspiracy theories over blogs and social media.

Lab accidents/zombies

28 Days Later and 28 Weeks Later

The 2002 film is often credited with sparking the 21st-century revival of the zombie genre, along with Resident Evil, released the same year. A highly contagious "Rage Virus" is accidentally released from a lab in Cambridge, England. Those infected turn into violent, mindless monsters who brutally attack the uninfected—so-called "fast zombies." Transmitted by bites, scratches, or even just by getting a drop of infected blood in one's mouth, the virus spreads rapidly, effectively collapsing society. A bicycle courier awakens from a coma 28 days later to find London mostly deserted, apart from a handful of survivors fleeing the infected hordes, and joins them in the pursuit of safety.

"I think the human mind deals with the dynamics of a zombie outbreak in ways that are very similar to the way we deal with any kind of infectious outbreak," Scrivner said of this category. "Zombies give off cues of disgust, of infection. Their skin is kind of flaking, they're doing things that are irrational." Because most zombie movies start off with a virus as the point of origin, he narrowed the category down to zombie outbreaks that originated in laboratory accidents.

This is the first (loose) film adaption of the video game series of the same name, in which a young woman with amnesia joins up with a band of commandos to contain a deadly outbreak of the fictional genetically engineered "T-virus." She is the sole survivor of the original outbreak in an underground genetic research lab known as the Hive, which turned the staff into zombies. The mission is to break into the Hive, shut down the lab's supercomputer, and close the facility before the virus threatens to overrun the entire Earth.

Just as the virus in 28 Days Later was the result of a lab accident, jumping from monkeys to people, in Resident Evil, a corporation develops an immune-system-boosting virus that mutates and then gets out into the population when it is purposely released by a thief. "These films speak to people's curiosity about, what would this look like if this was a lab accident?" said Scrivner. "And again, what do people do? Do they cooperate? Do they not cooperate when facing a universal threat? We're interested in how people are going to behave, because it's one more variable we have to control for that we're not used to controlling for in our daily lives."

Quarantine

This is the second installment in the popular Cloverfield franchise. The original 2008 film featured a Godzilla-like monster attacking New York City, releasing parasites that bit people, causing them to bleed from the eyes and then, well, explode. The US military attempts to destroy the monster by bombing Manhattan to bits. 10 Cloverfield Lane takes place in rural Louisiana, where a young woman wakes up from a car crash and finds herself in an underground bunker with two men. They tell her it's not safe to go above ground, since the air is filled with radiation from a recent nuclear or chemical attack. Three relative strangers cooped up underground indefinitely to avoid an unseen danger, who don't entirely trust each other? That's a recipe for disaster.

"These people have no idea what's going on outside. They don't know if there's a nuclear fallout, if it's a virus," said Scrivner. "It gives you this scenario in which you're stuck in a place, and you can't leave. I'm guessing this is the first time in many people's lives that they've been quarantined, so it's a scenario that people are really interested in learning about. What is it supposed to look like when people are quarantined? What are the possible variables?" (Spoiler alert: the biggest variable is aliens.)

Those Brits certainly have a knack for making taut, psychological thrillers about ordinary people dealing with extraordinary circumstances. Containment takes place in a council block of apartments (flats) in Southampton. The residents wake up one morning to find they have been sealed inside their homes, with no electricity or running water and no way to communicate with the world outside. They can see people in hazmat suits patrolling the grounds through their windows, however, and there is a voice over the intercom repeatedly telling them to stay calm and stay indoors.

"Containment is about a virus, about people who find they are quarantined inside their apartments," said Scrivner. "So they start to get a little stir crazy and decide to cooperate to break out of their own apartments." Sure, it's breaking quarantine and putting lives at risk (not just their own), but as we've seen in our current pandemic, fear and panic can bring out the worst in people, causing them to behave irrationally—and often violently.

Fear of outdoors

arstechnica

[contfnewc] [contfnewc]