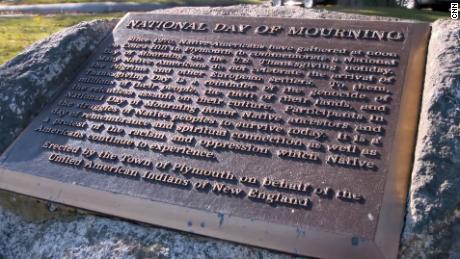

"The Pilgrims had hardly explored the shores of Cape Cod for four days before they had robbed the graves of my ancestors and stolen their corn and beans," reads a line from the remarks that Aquinnah Wampanoag tribal leader Wamsutta Frank James had planned to give.But event organizers wouldn't allow it — even 350 years after the cross-cultural feast that most Americans learn is at the root of Thanksgiving."When he presented it to them, they said, 'Well, we can't allow you to read that 'cause 90% of the people would walk out," Tall Oak, a member of the Aquinnah Wampanoag tribe, recalled to CNN.Wamsutta was asked to rewrite the speech, but he refused. "So, he withdrew," Tall Oak said.As word spread of that outcome, so was born the National Day of Mourning, a sort of counter-commemoration that happens every fourth Thursday of November. Now in its 50th year, the custom involves a few hundred Native Americans and nonnative people gathering on Cole's Hill, overlooking Plymouth Rock, to consider Thanksgiving from the perspective of Native Americans. A plaque at the site notes: "Thanksgiving Day is a reminder of the genocide of millions of their people, the theft of their lands, and the relentless assault on their cultures. Participants in National Day of Mourning honor Native ancestors and the struggles of Native peoples to survive today." "We go there every year, along with many nonindigenous allies, as well, to talk about the truth about Thanksgiving," said Mahtowin Munro, co-leader of the United American Indians of New England. "We still have to retell the story because it's still not known well enough," she said. "But I do think that more and more, nonnative people are listening and learning and are interested in the truth about what has happened."

Native Americans went to Plymouth to avert attack

Illustrations of what the first Thanksgiving might have looked like often depict Massasoit Ousamequin, the leader of the Wampanoag tribe, accepting an invitation from the Pilgrims of Plymouth to join them in a feast. Then, early settlers and Native Americans break bread side by side."There's this whole Norman Rockwell fantasy of what Thanksgiving was about, that it was this huge celebration between the first settlers and the tribes that sat down and talked, and that really wasn't the case," said Cedric Cromwell, chairman of the Wampanoag tribe.In reality, the Pilgrims were preparing to attack, he said.  "We sent 90 men over to the first settlers to see why they were shooting guns and practicing arms to say, 'Hey, what are you preparing for?' And they were preparing for some kind of war to take our people down," he said. "So, we sat down with them to have a discussion, and (that) led (to) a feast."Popular lore, he said, often also skips 17th-century realities: The Wampaonag were crucial to new settlers' survival that first winter, and the tribe had its own government, culture and religious beliefs. Scant recognition of those facts has led some Wampanoag tribal elders to believe Thanksgiving shouldn't be celebrated at all as a holiday. "It's the one day out of the year when all of America bows their heads and gives thanks for all that was taken from us," Tall Oak said.

"We sent 90 men over to the first settlers to see why they were shooting guns and practicing arms to say, 'Hey, what are you preparing for?' And they were preparing for some kind of war to take our people down," he said. "So, we sat down with them to have a discussion, and (that) led (to) a feast."Popular lore, he said, often also skips 17th-century realities: The Wampaonag were crucial to new settlers' survival that first winter, and the tribe had its own government, culture and religious beliefs. Scant recognition of those facts has led some Wampanoag tribal elders to believe Thanksgiving shouldn't be celebrated at all as a holiday. "It's the one day out of the year when all of America bows their heads and gives thanks for all that was taken from us," Tall Oak said.

The Wampanoag are 'still fighting for our rights'

Native Americans today face disparities in employment and wealth. Indigenous people also have the highest rate of Read More – Source