Update: It's Labor Day in the US, which means Ars staff are more likely to be monitoring a grill than breaking news throughout the day. As such, we're resurfacing a few classic stories from the archives, such as this from our old "First Encounter" series, which revisited those moments in which we first came across some new bit of tech that would eventually change our lives. This story originally ran on December 22, 2012, and it appears unchanged below.

I had seen glimpses of it as I walked past on my way to AP Geometry, but now I was about to enter the school computer lab for the first time.

It was September 1980 and my freshman year at Gateway High School had been knocked off-kilter barely a week into the first term. I had signed up for Russian 1, which involved a daily bus ride to the nearby high school in Aurora, Colorado where it was offered. My excitement at learning the language of the enemy during the height of the Cold War dropped considerably when only four students—from across the entire school district—showed up the first day of class. Such low enrollment meant Russian was cancelled a few short days later, forcing me to rework my schedule. I substituted Latin for Russian—which eliminated the need to hop on a bus each day— and that in turn opened a spot on my schedule for Introduction to Computer Programming.

My children have a hard time grasping this, but in 1980 the only computing devices I ran into on a daily basis were either calculators or video games. Sure, I might get a glimpse of the mainframe in the school office now and again, but my hands-on computing time happened either on my Sears-branded Intellivision knock-off or at the local arcade.

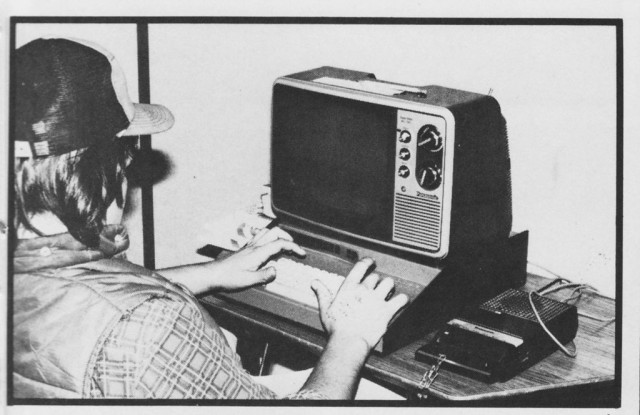

The computers in the lab at Gateway were unlike any Id seen before. They were blue metal boxes with black keyboards and 9" black-and-white TVs perched on top, and several were hooked up to teletypes. Chained to the desk next to them were cheap cassette tape decks. Big block letters informed me that these were Ohio Scientific Challenger 2P computers.

Priced at $495, the Challenger 2P sported a whopping 4KB of RAM, a 32×32 character display, and support for Microsoft BASIC—all powered by a MOS Technology 6502 processor running at 1MHz. Even by the standards of the day, these tech specs were a bit underwhelming. (The Apple ][+ came out the same year as the 2P—1979—and offered up to 16KB of RAM and 16 color graphics at 40×48 characters.) But that didnt matter to me, because I now had access to a computer. And I could make it do whatever I wanted.

We started the class with basic BASIC programming, simple stuff really.

10 A=1 20 B=10 30 A=A+1 40 C=A*B 50 IF A>10 THEN GOTO 80 60 ?A" X "B" = "C 70 GOTO 30 80 END

Then we moved on to for-next loops:

10 B=10 20 FOR A=1 TO 10 30 C=A*B 40 ?A" X "B" = "C 50 NEXT A

Boring? Well, kind of. But one day I wandered by the computer lab during lunch and saw an upperclassman playing what looked like a game. A little USS Enterprise was being guided by keyboard presses across the TV screen as it avoided a bunch of asterisks. The game was primitive, even compared to my next door neighbors Atari 2600, but the student had written it himself.

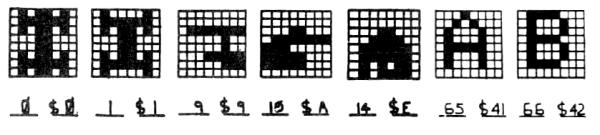

The video shown on the 9” black-and-white TVs used 1KB of memory. That 32×32 display worked out to 1,024 characters, but only 576 would actually show up (the rest were reserved as a sort of guard buffer). It was possible to write directly to the display, check to see if a given spot on the screen contained a particular character, and move characters around the display with the keyboard. I was immediately and irrevocably sucked in.

My spare time at school became devoted to successfully mixing the Star Wars and Star Trek universes by writing a two-player game that pitted the USS Enterprise against a TIE fighter (represented by a left-arrow and a right-arrow symbol). Should a phaser (hyphen) shot from the Enterprise score a hit, the TIE fighter would blow up—well, not so much "blow up" as be transformed into a pair of asterisks.

This snippet from Challenger 2P game Tank For Two offers an idea of what my own code looked like:

390 POKE P1,TA(T1) 400 FOR X=1TO3:IF F1=0 THEN 460 410 IF B1<>P1 THEN POKE B1,32 420 P=PEEK(B1+M1):IF P=161 THEN F1=0:GOTO 460 430 B1=B1+M1:POKE B1,BD(T1) 440 IF P=TA(T2)THEN F1=0:B1=P1:S1=S1+1:GOTO 460 450 IF B1C2 THEN F1=0 460 IF F2=0 THEN 520

The POKE command was used to render a particular character on the display, with the variable to the left of the comma representing the location in memory and the one to the right the character to be inserted there. PEEK was used to read the contents of a point in memory, determining whether the laser shot from the tie fighter scored a hit on the Read More – Source