It's possible to tell the difference between an American whiskey and other whiskeys just by studying the residual patterns left behind by the American variety as it evaporates, according to a new paper in Physical Review Fluids. Liquors like Scotch whisky, moonshine, and Irish whiskeys don't leave these telltale patterns, or "whiskey webs," when they evaporate.

As any connoisseur could tell you, the difference between Scotch whisky and American whiskey is more than just a single letter. "Scotch whisky typically acquires its flavor while it ages in mature—often recycled—barrels, while American whiskey, such as bourbon, is aged in new, charred-oak barrels," Matteo Rini wrote at APS Physics. "Understanding what this means at the chemical level could help with spotting illegal counterfeits and suggest faster alternatives to traditional aging." (Corn whiskey is an exception among the American varieties; it does not require wood aging at all.)

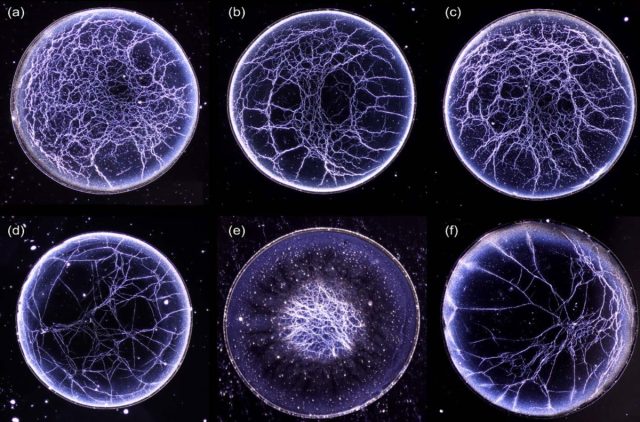

Co-author Stuart Williams, a professor of mechanical engineering at the University of Louisville in Kentucky, noticed one day that if he diluted a drop of bourbon and let it evaporate under carefully controlled conditions, it formed what he terms a "whiskey web": thin strands that form various lattice-like patterns, akin to networks of blood vessels. Intrigued, he decided to investigate further with different types of whiskey—plus a bottle of Glenlivet Scotch whisky for comparison. It was the perfect project for his sabbatical leave to study colloids (suspended particles in a medium, like Jell-O, whipped cream, tea, wine, and whiskey) at North Carolina State University.

Williams was also inspired in part by an earlier collaboration between Princeton University physicist Howard Stone and a Phoenix-based photographer named Ernie Button. Button's wife loved her whisky, so he began taking photographs of the intricate patterns that formed on the bottom of the glass as the liquid evaporated. Fundamentally, it's the same underling mechanism as the "coffee ring effect," when a single liquid evaporates and the solids that had been dissolved in the liquid (like coffee grounds) form a telltale ring. It happens because the evaporation occurs faster at the edge than at the center. Any remaining liquid flows outward to the edge to fill in the gaps, dragging those solids with it.

Mixing in solvents (water or alcohol) reduces the effect, as long as the drops are very small. Large drops produce more uniform stains. When Stone tracked the fluid motion in whiskey drops with fluorescent markers, he found that surfactant molecules collected at the edge of the drop. This created a tension gradient pulling the liquid inward (known as the Marangoni effect, which is also associated with "tears of wine"). There are also plant-based polymers that stick to the glass and channel particles in the whiskey. But whiskey chemistry is incredibly complicated, so what precise ingredients are associated with those two effects is still unclear.

Williams and his co-authors carefully deposited tiny drops of each type on a glass slide and took images as the liquid evaporated with an inverted microscope and LED back-illumination. Temperature and humidity were carefully controlled.) They noted considerable turbulence (eddies) in the first phase of evaporation, before things settled down into more of a laminar flow, akin to the wake generated by a ship. That initial turbulent phase helps determine the eventual pattern that forms. Chemicals are released as the whiskey interacts with the charred wood of the barrel. They form clumps (micelles), and the evaporative turbulence causes them to collapse into the final residual pattern.