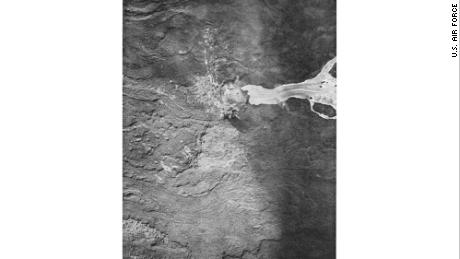

Once fissures open and the hot stuff starts flowing, it's best not to fight nature. "The flows cannot be stopped, but people have tried in the past," said Benjamin Andrews, director of the Global Volcanism Program at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History. Flows can and have been diverted though. The most famous example, Andrews cites, was in 1973 when the Eldfell volcano exploded on Heimaey, a small island in Iceland. "In that event, huge pumps were used to spray the advancing lava with seawater — but this effort did not stop the flow, rather it redirected the flow and prevented it from inundating the harbor," he said, adding that portions of some towns were overrun with lava. One person died as a result of the eruption.In other cases, explosive bombs were used in attempts to divert a lava flow. One such example was in 1935 when a volcanic eruption on Mauna Loa sent lava toward the town of Hilo, on Hawaii's Big Island. Famed military leader George S. Patton, then a lieutenant colonel, oversaw a US Army operation in which military planes dropped bombs near the vent that was the source of the lava, according to the US Geological Survey.The eruption ended six days later, but the effectiveness of disrupting lava channels with bombs remains in dispute, the USGS said.After another Mauna Loa eruption in 1942, the US military bombed the channel walls of the lava flow. There were no significant effects, according to a research paper on the topic published in the Bulletin of Volcanology.  Three days after the bombing, the spatter cone around the main lava vent partially collapsed by natural processes and caused the main lava flow to cease movement, the paper's authors said.

Three days after the bombing, the spatter cone around the main lava vent partially collapsed by natural processes and caused the main lava flow to cease movement, the paper's authors said.

Challenges

There are several challenges in stopping lava flow, according to Andrews of the Smithsonian. For starters, lava is dense."It may flow like sticky syrup, but is more dense than cement," he said. There's no point in putting up Jersey walls in front of a flow, he said, because the lava will "bulldoze them out of the way." Some have thought to spray the lava flow with water, hoping it will cool and freeze the front of the flow. But the extreme heat behind the crust, which is still molten, will allow the flow to continue. Andrews said that flows can be diverted, but then there's the dilemma of where the diverted lava goes. "This problem is most easily illustrated with the example situation where I divert the lava flow to save my house, but as a result, the lava flow destroys someone else's house," Andrews said. "As a result of these two factors, lava flows are generally not stopped or diverted."

There are several challenges in stopping lava flow, according to Andrews of the Smithsonian. For starters, lava is dense."It may flow like sticky syrup, but is more dense than cement," he said. There's no point in putting up Jersey walls in front of a flow, he said, because the lava will "bulldoze them out of the way." Some have thought to spray the lava flow with water, hoping it will cool and freeze the front of the flow. But the extreme heat behind the crust, which is still molten, will allow the flow to continue. Andrews said that flows can be diverted, but then there's the dilemma of where the diverted lava goes. "This problem is most easily illustrated with the example situation where I divert the lava flow to save my house, but as a result, the lava flow destroys someone else's house," Andrews said. "As a result of these two factors, lava flows are generally not stopped or diverted."

The aftermath

The lava has flowed, and the damage is done. Now there's the rock left behind from the flow. "In most instances, the rock is left in place," Andrews said because of its volume and the high cost of the effort required to break it apart and remove it.  But sometimes, it needs to be done. In October 2014, during a Kilauea volcano eruption, lava crossed over a major road called Cemetery Road, according to the Hawaii County Public Works Department. Crews removed the lava that blocked the roadway, and a restoration project began. The solidified lava became an attraction for a while, CNN affiliate KHNL in Honolulu reported. The project to remove the lava and restore Cemetery Road began in October 2015 and was completed that December. The project, public works said, was completed within the $150,000 budget.

But sometimes, it needs to be done. In October 2014, during a Kilauea volcano eruption, lava crossed over a major road called Cemetery Road, according to the Hawaii County Public Works Department. Crews removed the lava that blocked the roadway, and a restoration project began. The solidified lava became an attraction for a while, CNN affiliate KHNL in Honolulu reported. The project to remove the lava and restore Cemetery Road began in October 2015 and was completed that December. The project, public works said, was completed within the $150,000 budget.

CNN's Paul P. Murphy, Eric Levenson and Susannah Cullinane contributed to this report.

Original Article

[contf] [contfnew]

CNN

[contfnewc] [contfnewc]