In June, archaeologists began unearthing a Viking ship from a farmer’s field in eastern Norway. The 1,000- to 1,200-year-old ship was probably the grave of a local king or jarl, and it once lay beneath a monumental burial mound. A 2018 ground-penetrating radar survey of a site called Gjellestad, on the fertile coastal plain of Vikiletta, revealed the buried ship.

The Norwegian Institute for Cultural Heritage Research, or NIKU, announced the ship find in 2018, and it announced earlier in 2020 that excavations would begin over the summer to save the vessel from wood-eating fungus. NIKU archaeologist Lars Gustavsen and his colleagues’ recent study is the first academic publication of the survey results, and it includes the previously announced Gjellestad ship burial as well as the other ancient tombs and buildings. In the recently published paper, the radar images reveal the ghosts of an ancient landscape surrounding the royal tomb: farmhouses, a feasting hall, and centuries of burial mounds.

Altogether, the buried structures suggest that over several centuries, from at least 500 BCE to 1000 CE, an ordinary coastal farming settlement somehow grew into an important seat of power on the cusp of the Viking Age.

A ghost map of the past

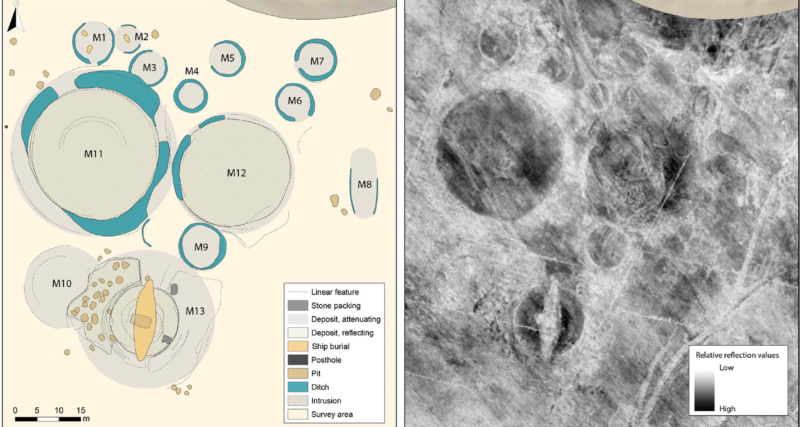

In 2018, archaeologists from NIKU crisscrossed the fields of Gjellestad with a ground-penetrating radar unit mounted on the front of an all-terrain vehicle. They revealed a forgotten Iron Age world beneath the crops and pastures. In the radar images, a dozen ghostly rings mark the loose soil filling in ditches that once ringed burial mounds. Postholes and wall foundations trace the faint outlines of at least three former farmhouses, along with a larger building that could be an Iron Age feasting hall.

There, the local landowner would have held feasts, political assemblies, and some religious gatherings (though others would have taken place outdoors). A proper feasting hall wasn’t something most farms or small communities would have had; only wealthy, powerful landowners could have built one or would have had any reason to do so. The hall would have marked Gjellestad as an important meeting point for religious events and business as well as a center of political power for the whole region.

Radar images show postholes that once held wide, hefty support timbers, standing in two parallel rows along the middle of a 38-meter-long building, with two large rooms in the center. That’s unusually large for a farmhouse but just about right for a feasting hall. And just across a fence from the hall, to the east, stood four large burial mounds, including the Gjellestad ship grave.

Ties to the land were very important in Scandinavian culture. People considered it very important to maintain a connection with the land where their ancestors were buried, for instance. All the construction at Gjellestad would have been a strong statement about the ruling family’s hold on their lands and their power in the tumultuous centuries leading up to the Viking Age.

Local farmstead makes it big

The layout of the feasting hall—specifically, the way its walls curve outward slightly—suggest that it may date to sometime between roughly 500 and 1100 CE. It’s impossible to be more precise without actually digging up artifacts to radiocarbon date, but based on comparisons with other sites, the largest burial mounds at the site, including the ship grave, probably date to the same broad timeframe.

By then, the community at Gjellestad was probably centuries old, having started out as a more ordinary farming community with a fairly typical cemetery of burial mounds nearby. The 2018 radar survey revealed the ring-ditch footprints of nine smallish mounds (about 7 meters to 11 meters wide) at Gjellestad, and archaeologists already knew about dozens more mounds roughly a kilometer from the site.

These mounds probably would have held the dead ancestors of those who lived and farmed nearby. One mound at Gjellestad, dubbed M8, may actually belong to a woman; its long oval shape resembles tombs of women from other Iron Age mound cemeteries in Norway. Radar images show features which might be the actual graves buried at the center of the former mounds.

And the images are detailed enough to reveal literal layers of history beneath the fields of east Norway. Gustavsen and his colleagues could see that people at Gjellestad had built their large burial mounds overlapping the sides of smaller mounds. That suggests the smaller mounds were there first.

“This might just be a result of coincidence or practical circumstances,” Gustavsen told Ars. “Another interpretation is that it is a way of associating oneself with an existing cemetery, or perhaps as a more forceful statement where an incoming elite wants to establish themselves in the landscape and do so by placing their burial mounds on top of existing ones.”

Again, it’s impossible to say for sure how old any of the mounds are without excavating them, but the larger ones probably date to the centuries just before and during the Viking Age, 500 to 1100 CE, based on comparisons with other sites. The smaller mounds may be centuries older than that. At least two of the farmhouses may be the same age as the smaller mounds, based on their layout.

Work in progress

Excavating the Gjellestad ship is likely to take about another month, Gustavsen said. The Gjellestad ship offers archaeologists their first chance to excavate and study a Scandinavian ship in over a century. It’s one of just four ship burials in Scandinavia, including the one spotted last year by an aerial GPR survey in western Norway. Only about 19 meters of the vessel’s hull remain, but in “life” it was probably 22 meters from stem to stern—a proper oceangoing vessel of the kind that would eventually carry the Vikings to shores from Greenland to Constantinople.

Meanwhile, Gustavsen hopes to be able to do more ground-penetrating radar surveys of the landscape around Gjellestad to try to understand more about how the burial mounds, the farmhouses, and the feasting hall fit into the larger world of Iron Age Norway.

“What happens to the site and this particular field in the future is not clear,” Gustavsen told Ars. These discoveries happened because, in 2017, a local farmer filed for a permit to dig a drainage ditch in one of their fields. “The landowner has been positive to the process and has been informed and involved from the start,” said Gustavsen. “At the moment, the landowner is being compensated for lost income, but obviously that cannot go on forever.”

The people who farm the Vikiletta Plain today know they’re walking atop the houses, halls, ritual sites, and graves of centuries past. Most of the burial mounds and standing stones that once dotted the gently sloping landscape vanished beneath 19th-century plows, but modern farmers occasionally turn up artifacts in their fields, and crops tend to grow higher and greener over buried ditches.

Archaeologists unearthing the Gjellestad ship are working practically in the shadow of one of the largest burial mounds in Scandinavia, known as the Jell Mound, probably the resting place of an Iron Age ruler. Like much of the ancient landscape of the region, it had faded into the background of modern life. “It was perhaps a little bit forgotten—it was something you passed on the motorway on your way to Sweden,” Gustavsen told Ars. "Hopefully people will eventually start seeing these sites as valuable assets that can be an enrichment to a place."

Antiquity, 2020 DOI: 10.1584/aqy.2020.39 (About DOIs).