Update January 17, 2018, 8:12 ET: Yesterday the Office of the Governor of Hawaii sent Honolulu Civil Beat a screenshot of what it said was a list of options that employees saw when they sent out alerts to citizens. The bad layout and confusing wording made it clear that the employee was less to blame than bad design.

But late Tuesday the Governor’s office told Honolulu Civil Beat that it circulated a false image. "We asked (Hawaii Emergency Management Agency) for a screenshot and that’s what they gave us," Governor’s office spokeswoman Jodi Leong told Civil Beat. "At no time did anybody tell me it wasn’t a screenshot."

It’s unclear what the original image reflects, but Hawaii Emergency Management (HI-EMA) Administrator Vern Miyagi allegedly texted Leong the image below, which was widely circulated as an example of the kind of bad design that would trip up anyone, even if they were sending a test missile alert to millions.

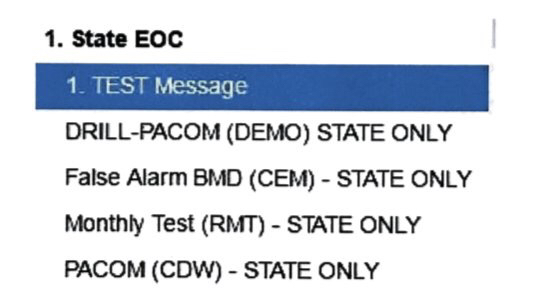

Instead, on Tuesday, HI-EMA’s public information officer offered a second image, which is apparently a mock-up closer to what an HI-EMA employee might see. The agency said a true screenshot couldn't be shared due to security concerns. The mock-up suggests the real interface is less bad than the first but still hardly a shining example of good design.

Original Story, January 16, 2018, 13:00 ET: The Honolulu Civil Beat claims to have obtained a picture of the interface used to send out tests and missile alerts to the people of Hawaii, and it's not pretty.

It appears the employee who sent out the mobile and broadcast missile alert that sent Hawaii into a panic for 38 minutes on Saturday was supposed to choose "DRILL – PACOM (CDW) – STATE ONLY" but instead chose "PACOM (CDW) – STATE ONLY" from an unordered list of equally unintuitive and difficult-to-read options.

This is the screen that set off the ballistic missile alert on Saturday. The operator clicked the PACOM (CDW) State Only link. The drill link is the one that was supposed to be clicked. #Hawaiipic.twitter.com/lDVnqUmyHa

— Honolulu Civil Beat (@CivilBeat) January 16, 2018

The Honolulu Civil Beat noted in a story on Sunday that the employee who made the choice from the nearly unintelligible list has been temporarily reassigned within the Hawaii Emergency Management Agency (HI-EMA), and his status at the agency will be decided after a review. The news outlet wrote that according to Emergency Management Agency Administrator Vern Miyagi, the employee "felt terrible about the mistake."

One issue that prevented HI-EMA from correcting the missile alert immediately was that there was no automated way to send out a "false alarm" notification to the hundreds of thousands of people who received the Wireless Emergency Alert (WEA) or to the television and radio broadcast stations that also conveyed the grave warning. Instead, the agency had to send a correction manually.

In the aftermath of the confusion, the agency said that two people would now be required to sign off on an alert or a drill message. In addition, an automated "false alarm" message had been added to the alert system.

According to Honolulu Civil Beat, that automated "false alarm" message is now at the top of the menu of the still-bad alert interface.

The BMD False Alarm link is the added feature to prevent further mistakes #Hawaiipic.twitter.com/wdjVVJoych

— Honolulu Civil Beat (@CivilBeat) January 16, 2018

If a future employee is just as perplexed by the menu below, at least now they can select "BMD False Alarm" to cancel a missile alert more quickly.

That the interface helping employees select such vital and potentially world-changing information is so rudimentary is concerning, but false missile alarms are hardly unique to Hawaii. In fact, just this morning, Japanese broadcaster NHK accidentally sent a push alert to users of the NHK app saying "NHK news alert. North Korea likely to have launched missile. The government J alert: evacuate inside the building or underground." NHK issued a correction "within minutes" and apologized, according to CNN, but the fact that the alert was the second mistake in five days suggests there's work to be done.

[contf] [contfnew]

Ars Technica

[contfnewc] [contfnewc]