The clearest way out of the COVID-19 crisis is to develop a safe, effective vaccine—and scientists have wasted no time in getting started.

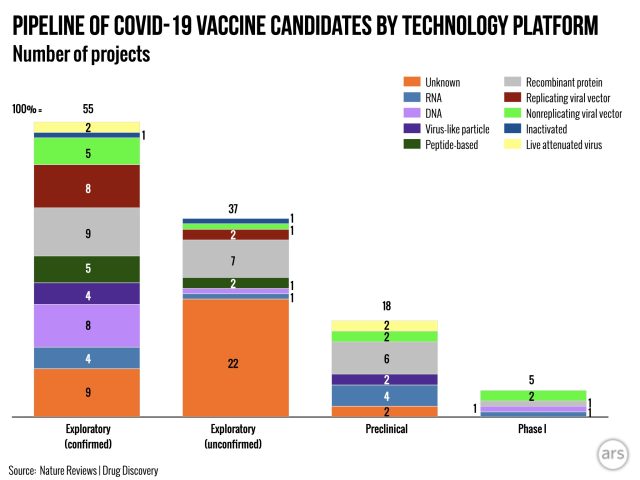

They have at least 102 vaccine candidates in development worldwide. Eight of those have already entered early clinical trials in people. At least two have protected a small number of monkeys from infection with the novel coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, that causes COVID-19.

Some optimistic vaccine developers say that, if all goes perfectly, we could see large-scale production and limited deployment of vaccines as early as this fall. If true, it would be an extraordinary achievement. Less than four months ago, SARS-CoV-2 was an unnamed, never-before-seen virus that abruptly emerged in the central Chinese city of Wuhan. Researchers there quickly identified it and, by late January, had deciphered and shared its genetic code, allowing researchers around the world to get to work on defeating it. By late February, researchers on multiple continents were working up clinical trials for vaccine candidates. By mid-March, two of them began, and volunteers began receiving the first jabs of candidate vaccines against COVID-19.

Its a record-setting feat. But, its unclear if researchers will be able to maintain this break-neck pace.

Generally, vaccines must go through three progressively more stringent human trial phases before they are considered safe and effective. The phases assess the candidates safety profile, the strength of the immune responses they trigger, and how good they are at actually protecting people from infection and disease.

Most vaccine candidates dont make it. By some estimates, more than 90 percent fail. And, though a pandemic-propelled timeline could conceivably deliver a vaccine in as little as 18 months, most vaccines take years—often more than 10 years, in fact—to go from preclinical vetting to a syringe in a doctors office.

Abridging that timeline can up the risk of failure. For instance, vaccine candidates usually enter the three phases of clinical trials only after being well tested in lab animals that can model the human disease. But, with such a new virus, there is no established animal model for COVID-19. And amid a devastating pandemic, theres not enough time to thoroughly develop one. Some researchers are now doing that ground-level animal work in parallel with human trials—such as the small monkey trials mentioned above.

Researchers already have reason to be a little anxious about the safety of any COVID-19 vaccine. When they tried in the past to make vaccines against some of SARS-CoV-2s coronavirus relatives, they found a small number of instances when candidate vaccines seemed to make infections worse. That is, these candidate vaccines seemed to prompt berserk immune responses that caused lung damage in monkeys and liver damage in ferrets. Researchers still dont fully understand the problem and dont know if it could happen in humans, let alone if it will show up with the new candidate vaccines against SARS-CoV-2.

But we may soon know the answers. As the pandemic tops the grim milestone of three million cases worldwide and well over 200,000 deaths, researchers are relentlessly moving forward with vaccine development. Here's where the scientific community currently stands in its frenetic effort.

First, the basics

Researchers are using a wide variety of tools and techniques to develop a vaccine—some are tried and tested, others are fresh and unproven. Regardless of the strategy, they all aim to do the same thing: train the immune system to identify SARS-CoV-2 (or some element of it) and destroy it before it establishes an infection and causes COVID-19.

The way a vaccine can pull this off, typically, is by feeding immune cells a signature element of a disease-causing germ, such as a unique protein that coats the outside of a dangerous virus. From there, a type of white blood cell called B cells can generate antibodies that specifically recognize and glom onto those signature germ elements. Antibodies are Y-shaped proteins, which have their germ-specific detecting regions on their outstretched arms. The base of their “Y” shape is a generic region that can signal certain immune responses if they detect an invading germ.

A strong, effective vaccine can generate so-called neutralizing antibodies. These antibodies circulate in the blood, surveilling the whole body after a vaccine is given. If the germ theyre trained to detect actually shows up, the antibodies can swarm and paralyze it. The base of the antibodies—now dangling off their smothered target germ—can then signal immune cells to help finish the job.

In the case of COVID-19, the goal of candidate vaccines is to train our immune systems to make antibodies that specifically detect and destroy SARS-CoV-2 (which is, again, the novel coronavirus that causes COVID-19). Though theres a lot we dont know about SARS-CoV-2, we know enough of the basics to direct early vaccine development.

We know that SARS-CoV-2 is a betacoronavirus related to two other notorious betacoronaviruses: SARS-CoV-1, which causes SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome), and the Middle Eastern respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV), which causes MERS.

Coronaviruses, generally, keep their genetic blueprints in the form of a large, single-stranded, positive-sense RNA genome, which is bundled into a round viral particle. That genetic code provides the molecular instructions to make all of the components of the virus, including enzymes required to make copies of the viruss genome, and the viruss famous spike protein.

The spike protein is what the coronaviruses use to grab ahold of host cells—that is, human cells they infect or the cells of any other animal victim. Once the virus latches on with its spike protein, it gets into the cell and hijacks the cell's activities, forcing it to help manufacture viral clones, which then burst forth to infect more cells.

There are many copies of the spike protein on the outer surface of coronaviruses, creating a spikey exterior—think a cartoon sea mine. The pointy adornments are actually what give coronaviruses their name. Under an electron microscope, the spikes give the viral particle a crown-like appearance, hence corona viruses. But more importantly, the spike proteins are a prime target for antibodies. And, because we have the whole genome sequence for SARS-CoV-2, researchers have a good start at figuring out effective ways to engineer vaccines to attack the spike proteins and other critical components of the virus.

Vaccine platforms

There are many ways to try to train the immune system to fight off a specific germ or specific elements of germs, such as SARS-CoV-2 or the SARS-CoV-2 spike proteins. Here are the general categories currently in play:

Live-attenuated vaccine: These vaccines use whole viruses that are weakened so they can no longer cause disease. This is a well-established method for creating vaccines. In the past, researchers weakened viruses by growing them in lab conditions for long periods of time—which is a bit like domesticating germs. The cushy, all-inclusive petri-dish lifestyle can essentially allow viruses and bacteria to adapt to their tranquil surroundings and lose virulence over time. But, it can take a while. Scientists grew the measles virus in lab conditions for nearly 10 years before using it for a live-attenuated vaccine in the early 1960s.

Nowadays, there are faster, more controlled approaches to engineer weakened viruses, such as targeted mutations and other manipulations of a viruss genetic code.

Live-attenuated virus vaccines have the advantage of generating the same variety of protective antibodies as a real infection—without causing a pesky, life-threatening disease, for the most part. But there are risks. Because the virus can still replicate, certain people (particularly those with immunodeficiencies) may have severe reactions. Though the newer strategies for weakening viruses may reduce these risks, they still require extensive safety testing before reaching the market.

That said, this is a vaccine platform that has already proven successful. Several vaccines in use are live-attenuated vaccines, including vaccines for chickenpox and typhoid. If such a vaccine proved effective at preventing COVID-19, we already have the know-how and infrastructure to quickly scale up production to make these vaccines.

Inactivated vaccine: This is another straightforward, old-school method that uses whole viruses. In this case, the viruses are effectively dead, though, usually inactivated by heat or chemicals. These corpse viruses can still prime the immune system to make neutralizing antibodies; they just do it less efficiently.

The advantage of this strategy is that it is relatively simple to make these types of vaccines and, because the viruses dont replicate, there is no risk of infection and less risk of severe reactions. Disadvantages include that inactivated, non-replicating viruses dont illicit as strong of an immune response as a disease-causing or weakened virus. Inactivated vaccines always require multiple doses and may need periodic booster shots as well.

Like weakened virus vaccines, using a whole viral particle gives the immune system many potential viral targets for antibodies. Some may be good targets to neutralize a real infection, and some may not. But, using an inactivated virus is a proven method. For instance, some existing vaccines against polio, hepatitis A, and rabies use this method.

Viral vector-based vaccine: For these vaccines, researchers take a weakened or harmless virus and engineer it to contain an element of a dangerous virus they want to protect against.

In the context of COVID-19, this might mean engineering a harmless virus to produce, say, the spike protein from SARS-CoV-2. This way you get the immune response to a live but benign virus, coupled with the likelihood of having antibodies that target a specific critical protein from the dangerous SARS-CoV-2.

This, too, is a proven strategy for effective vaccines. The newly approved Ebola vaccine, for instance, uses this method.

Subunit vaccines: These are bare-bones vaccines that include only a component of a dangerous virus to elicit immune responses. For COVID-19 vaccines, the spike protein is—no surprise—a popular candidate.

Subunits can be delivered in formulations with adjuvants—accessory ingredients that can enhance immune responses. One common adjuvant is alum, an aluminum salt, long known to be useful for vaccines. Some newer subunit vaccines come in snappier packages, however. These include artificial “virus-like particles” (VLPs) and nanoparticles.

Subunit vaccines are already an established vaccine platform. The HPV vaccine in use involves a VLP that feeds the immune system proteins from the HPVs outer shell—which can then be targeted by antibodies.

RNA and DNA vaccines: These are among the newest types of vaccines—and among the shakiest. There are currently no licensed vaccines that use this method. But researchers are optimistic about their potential.

The basic idea is to deliver genetic material of a virus—either in the form of DNA or RNA—directly to human cells, which are then somehow compelled to translate that genetic code into viral proteins and then able to make antibodies against those.

Some of the details of how these candidate vaccines work are proprietary and unproven, so its difficult to assess how likely they are to succeed or how easy it will be to scale up vaccine production if they are successful.

Potential pitfalls

As mentioned earlier, in some previous work on developing a vaccine against SARS-CoV-1—the virus behind SARS—researchers came across a few instances where candidate vaccines seemed to make disease worse in animal models. This led to some instances of organ damage in a few animal models, namely monkeys, ferrets, and also mice.

So far, its unclear what was going on there. Some researchers have speculated that it may be a form of Antibody-Dependent Enhancement (ADE). Very generally, this is a scenario in which the immune system makes antibodies against an invading germ, but those antibodies are not able to neutralize the germ completely. This can make the situation worse if the shoddy antibodies signal for immune cells to respond while the germ is still infectious. Basically, the antibodies are just recruiting immune cells to be the germs next victims. And this, in turn, can lead to additional—excessive—immune responses that end up damaging the body.

One of the best understood examples of this occurs with dengue viruses. There are four types of dengue viruses that circulate (in people and mosquitoes), and research suggests that some antibodies to one type of dengue may sometimes generate ADE in subsequent infections or exposures with other types of dengue. This is why researchers think that some patients with dengue fever, which can be a mild disease, go on to develop dengue hemorrhagic fever. This is a rare but severe form of the disease in which immune cells release chemicals called inflammatory cytokines that end up damaging the circulatory system, leading to blood plasma leaking out of capillaries. From there, the patient can go into shock and die.

But, many researchers are not convinced that ADE is behind some of the problems seen with early SARS vaccines—nor that ADE will necessarily be an issue with a COVID-19 vaccine. For one thing, the berserk immune responses seen in the animal models dont seem to involve some of the same immune system components seen in well-understood cases of ADE, like dengue.

“Theres no clear evidence that ADE is an issue,” microbiologist Maria Elena Bottazzi tells Ars. Bottazzi is the associate dean of the National School of Tropical Medicine at Baylor College of Medicine.

Instead, Bottazzi and colleagues hypothesize that something about the coronaviruses and whole-virus vaccine candidates may induce an excessive, aberrant inflammatory response, potentially through the activity of specialized, pro-inflammatory immune cells called T helper 17 cells, which are linked to inflammatory autoimmune diseases. This may help explain why some patients with the most severe forms of COVID-19 seem to experience so-called “cytokine storms,” which are like a disastrous deluge of pro-inflammatory signals unleashed by the immune system that end up causing damage to the body—just like in the animal models.

Much of this is still speculative, but Bottazzi says what we know so far may be helpful for directing vaccine development strategies. She notes that the excessive immune responses may mainly occur when the immune system is presented with a whole, intact coronavirus particle. Something about interacting with that whole particle may send our Read More – Source

[contf] [contfnew]

arstechnica

[contfnewc] [contfnewc]