The confirmation of Brett Kavanaugh to the US Supreme Court last week raised fears of a hyper-partisan SCOTUS and loss of public trust in the institution—particularly in light of Kavanaugh's highly emotional and partisan testimony during the Senate hearing on the sexual assault allegations against him. But a new study offers a glimmer of hope, concluding that in the long run, there is more consensus than partisan difference in SCOTUS decisions.

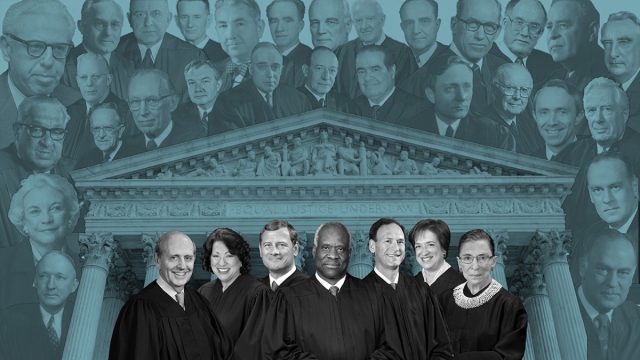

It's the first quantitative model to capture detailed correlations in voting patterns of the SCOTUS justices across time. Cornell University graduate student Eddie Lee created a hypothetical "Super Court" to study the voting patterns of Supreme Court justices serving from 1946 through 2016. Neither Kavanaugh nor the other recently confirmed justice, Neil Gorsuch, is included in the analysis, which was recently published in the Journal of Statistical Physics. It builds on Lee's 2015 study examining the voting patterns of the second Rehnquist court (1994-2005), which found justices were far more prone to unanimity in their decisions despite their ideological differences.

It might seem strange to create such a Super Court scenario, but Lee argues that it makes sense to do so, given how much different justices overlap with each other because of their lifelong tenure. So even if Justice A never actually voted with Justice C, both likely served at the same time (and thus voted with) Justice B. This makes it possible to infer from that when Justices A and C might have voted together.

"We might imagine that the justices are 'coupled' such that ferromagnetic couplings correspond to ideologically similar justices."

For his data analysis, Lee adapted a statistical model for magnetic behavior. "Just as the components of a magnet tend to either align (ferromagnetism) or anti-align (anti-ferromagnetism), we might imagine that the justices are 'coupled' such that ferromagnetic couplings correspond to ideologically similar justices," he said. Lee has found a way to make that metaphor quantitative by measuring the couplings found in the voting record. And he found that the voting patterns neatly correspond to the magnetism model.

There was some evidence in the data of partisan voting blocs amid shifting alliances along ideological lines, but Lee found this constituted a small fraction of the overall pattern on his hypothetical Super Court. Rather, any given justice would be found in a surprisingly varied range of voting blocs, even for what we might deem the most sharply partisan issues. Over time, the court defaults to consensus, with strong (and sometimes surprising) correlations among the justices.

The late 19th century SCOTUS justices under Chief Justice Morrison Waite, for instance, made 9-0 decisions about 90 percent of the time. While the court has become much less unanimous since the 1940s, Lee nonetheless found that unanimous decisions still occur between 30 percent and 50 percent of the time. That pattern of consensus spans nearly 100 years, an institutional timeline far longer than the tenure of even the longest-serving justices.

In other words, "The collective behavior of the court over time reveals a stable institution insulated from the seemingly rapid pace of political change," says Lee. It's in sharp contrast to the much more volatile voting patterns among members of Congress, who have much more frequent turnover rates.

All of this runs counter to the prevailing narrative of the daily news cycle, as well as the opinions of some Supreme Court scholars. "When one considers the complexity of voting across time, it doesn't make sense to think about left versus right," says Lee. "In the grand scheme of things, we may think of this particular Supreme Court as divided between left and right, but it is not clear what it means to call the institution partisan over long periods of time."

DOI: Journal of Statistical Physics, 2018. 10.1007/s10955-018-2156-0 (About DOIs).

[contf] [contfnew]

Ars Technica

[contfnewc] [contfnewc]