When Donald Trump launched Operation Warp Speed last week, he borrowed language from Star Trek to describe the drive for a Covid-19 vaccine. “That means big and it means fast,” the US president said, promising an effort “moving on at record, record, record speed.”

His hope that a coronavirus vaccine might be ready “prior to the end of the year” was even quicker than the optimistic—but often repeated—timeline for a vaccine to be ready in 12 to 18 months.

The race for a vaccine appeared to be picking up pace this week when Moderna, a Boston-based biotech company, unveiled early positive results for its potential vaccine in a small trial—and AstraZeneca said it could have the first doses of another vaccine delivered by October if trials are successful.

The announcements pleased politicians trying to offer hope to citizens desperate to leave lockdowns and investors eager for economic activity to return.

But many scientists feel a duty to damp the enthusiasm. They say a vaccine could take much longer because little is known about the disease and how bodies will react to attempts at immunization. In fact, some warn we may never create a vaccine for Covid-19.

Soumya Swaminathan, chief scientist for the World Health Organization, believes an optimistic scenario is a vaccine produced in the “tens of millions” next year, which would be mainly distributed to healthcare workers, and far larger volumes in 2022. To inoculate the world and defeat Covid-19 could take four to five years, she says.

We have no “crystal ball” to tell the future, she told the Financial Times. “It depends how the virus behaves: whether it mutates, whether it becomes more or less virulent, more or less transmittable.”

Peter Hotez, a professor at the Baylor College of Medicine in Houston who is developing a vaccine, says the US president sees vaccines as a “manufacturing problem,” like making enough ventilators or tests.

“Manufacturing is not the hurdle. Its taking the time to collect enough efficacy and safety data,” he says. “The Operation Warp Speed language coming out of the White House and biotechs and pharma companies [saying] that they will have a vaccine by the fall—or in weeks or days—does so much damage.”

Vaccines are usually developed over many years and even decades. A 2013 paper from Dutch scientists says the average vaccine took 10.71 years and had only a 6 per cent success rate from start to finish. Each stage is an experiment: from the small phase one trials happening now to the large phase three trials needed for regulatory approval.

There are good reasons to believe this time will be quicker. The Covid-19 vaccines benefit from groundwork done for the Sars and Mers coronaviruses even if they were never approved, says Walter Orenstein, a professor at the Emory Vaccine Center in Atlanta.

New technologies are fueling the hope for a faster process. Analysts from Morgan Stanley estimate that Modernas vaccine has a 65 percent chance of success. They believe that before the end of the year we could see vaccines from Pfizer and their German partner BioNTech, and AstraZeneca and Oxford university.

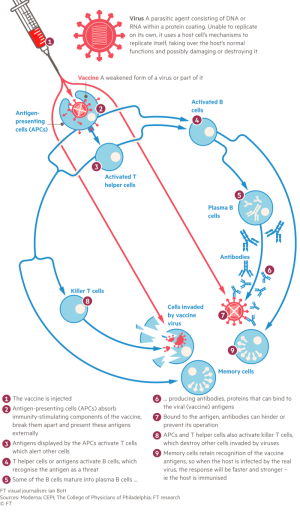

But advances like the messengerRNA programming used by Moderna, BioNTech and another German company, CureVac, have never been used to create products approved by a regulator. The technique translates a protein from the virus into human cells and shows it to the B cells that secrete antibodies.

The pandemic has pushed governments and companies to pour money into Covid-19 vaccines, even if there has been a lack of global cooperation. Peter Bach, director of the Center for Health Policy and Outcomes at Memorial Sloan Kettering, says it helps that there are so many horses in this race.

Proving that a vaccine is safe and effective takes time. Participants need to be exposed to the virus to prove a vaccine works. That probably means recruiting thousands of people across the world to ensure enough live in an area where there is an outbreak, unless vaccine makers opt for the ethically complicated human challenge trials, where participants are deliberately infected.

“I dont want to be a Debbie Downer but lets be clear: to get a vaccine by 2021 would be like drawing multiple inside straights in a row, to use a poker analogy,” Dr. Bach says.

To fight a war, it helps to know your enemy. Originally considered solely a respiratory disease, Covid-19 has launched surprise attacks from our eyes to our toes. It appears to use different tactics in children, with reports of some suffering from a serious inflammatory condition.

Moderna announced early results from its phase one trial on Monday, showing its vaccine had elicited immune responses at least as robust as those found in recovered patients.

But some scientists questioned how the trial defined an average patient response. Dr. Hotez says the release came days after a study showing that recovered patients only had a low level of antibodies. Umer Raffat, a biotech analyst at Evercore, says it will be important to know when the convalescent antibody level was tested—because it tends to fade over time. If it is tested later, it might not be such a promising comparison.

There are big questions about how long an immune response protects patients for. Most scientists think having had the disease confers some immunity—but we dont know how long it lasts. Immunity to Sars only lasted a couple of years.

So far, the virus behind Covid-19 has not mutated significantly, so it shifts shape less rapidly than the flu. But we have only been following the virus for months, so there is a risk that it will still mutate. Most vaccine makers are focusing on the spike protein, which it uses to invade cells. They try to teach the body to recognize this protein and produce antibodies. If the spike changes, many of the potential immunizations would miss their target.

Early trials are done in healthy, younger populations: Modernas first results were from people aged 18 to 55. But it is people over 65 who have suffered the most from Covid-19 and whose immune systems tend to be less responsive. The US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases is adding an older age group to the trial.

Howard Koh, a former US assistant secretary at the health department, says: “One issue that often comes up is whether older people are able to generate a response that makes it an effective vaccine.”

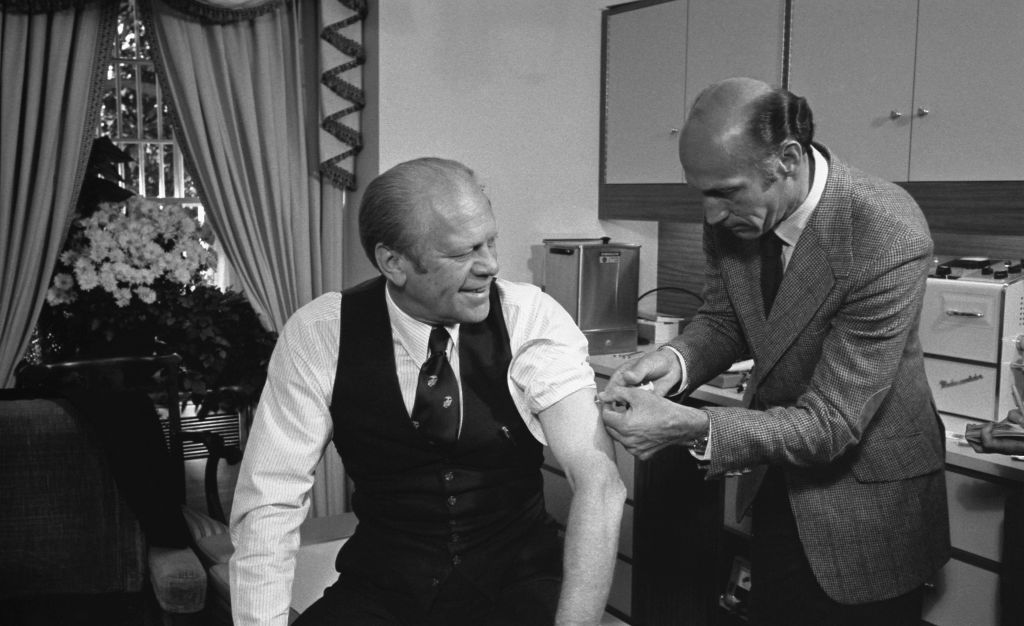

Mr. Trump is not the first president to see a vaccine as a way of neutralizing the political risk carried by a virus. In 1976, Gerald Ford rushed out a vaccine for what he feared would be a massive outbreak of swine flu, having his photo taken getting the shot at the White House. But the vaccine had a serious side-effect: hundreds of people developed Guillain-Barré syndrome, where the body is paralyzed by the immune system attacking the nerves.

Covid-19 has proven to be the pandemic that the 1976 swine flu never became. But easing requirements for approval could put vaccines on the market before we discover all the side-effects. In the US, the loosening of regulations during the pandemic haRead More – Source

[contf] [contfnew]

arstechnica

[contfnewc] [contfnewc]