It's fair to say that the Windows 10 October 2018 Update has not been Microsoft's most successful update. Reports of data loss quickly emerged, forcing Microsoft to suspend distribution of the update. It has since been fixed and is currently undergoing renewed testing pending a re-release.

This isn't the first Windows feature update that's had problems—we've seen things like significant hardware incompatibilities in previous updates—but it's certainly the worst. While most of us know the theory of having backups, the reality is that lots of data, especially on home PCs, has no real backup, and deleting that data is thus disastrous.

Windows as a service

Microsoft's ambition with Windows 10 was to radically shake up how it develops Windows 10. The company wanted to better respond to customer and market needs, and to put improved new features into customers' hands sooner. Core to this was the notion that Windows 10 is the "last" version of Windows—all new development work will be an update to Windows 10, delivered through feature updates several times a year. This new development model was branded "Windows as a Service." And after some initial fumbling, Microsoft settled on a cadence of two feature updates a year; one in April, one in October.

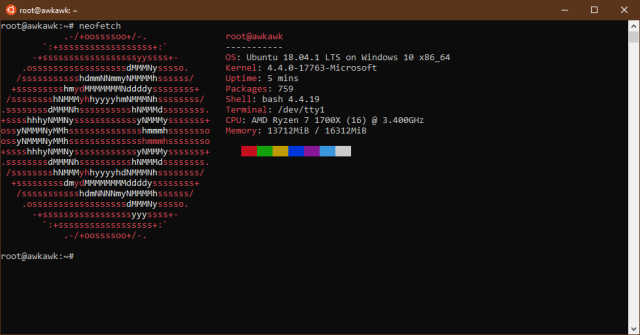

This effort has not been without its successes. Microsoft has used the new model to deliver useful new features without forcing users to wait three years for a new major version upgrade. For example, there's a clever feature to run Edge seamlessly in a virtual machine to provide greater protection from malicious websites. The Windows Subsystem for Linux (WSL), which equips Windows systems to run Linux software natively, has proven a boon for developers and administrators. The benefits for pure consumers may be a little harder to discern—though VR features compatible with SteamVR, improved game performance, and a dark theme, have all been nice additions. While the overall improvements are smaller, the current Windows 10 is certainly better than the one released three years ago.

This is a good thing, and I'd even argue that some parts of it could not have been done (or at least, could not have been done as successfully) without Windows as a Service. WSL's development, for example, has been guided by user feedback, with WSL users telling Microsoft of incompatibilities they've found and helping the company prioritize the development of new WSL features. I don't believe WSL could have received the traction it has without the steady progress of updates every six months—nobody would want to wait three years just to get a minor fix so that the package they care about runs properly. Regular updates reward people for reporting bugs, because they can actually see those bugs resolved in a timely manner.

The problem with Windows as a Service is quality. Previous issues with the feature and security updates have already shaken confidence in Microsoft's updating policy for Windows 10. While data is notably lacking, there is at the very least a popular perception that the quality of the monthly security updates has taken a dive with Windows 10 and that installation of the twice-annual feature updates as soon as they're available is madness. These complaints are long-standing, too. The unreliable updates have been a cause for concern since shortly after Windows 10's release.

The latest problem has brought this to a head, with commentators saying that two feature updates a year is too many and Redmond should cut back to one, and that Microsoft needs to stop developing new features and just fix bugs. Some worry that the company is dangerously close to a serious loss of trust over updates, and for some Windows users, that trust may already have been broken.

These are not the first calls for Microsoft to slow down with its feature updates—there have been concerns that there's too much churn for both IT and consumer audiences alike to handle—but with the obvious problems of the latest update, the calls take on a new urgency.

It's not how often, it's how

But saying Microsoft should only produce one update a year instead of two, or criticising the very idea of Windows as a Service, is missing the point. The problem here isn't the release frequency. It's Microsoft's development process.

Why is it the process, and not the timeframe, that's the issue? On the release schedule front, we can look at what other software does to get a feel for what's possible.

Two updates a year is more frequent than macOS, iOS, and Android, so in a sense Microsoft is attempting to overachieve. But it's not unprecedented: Ubuntu sees two releases a year, and Google's Chrome OS, like its Chrome browser, receives updates every six weeks. Beyond the operating system space, Microsoft's Office Insider program has a monthly channel that delivers new features to Office users each month, and it manages to do so without generating too many complaints while delivering a steady trickle of new features and fixes. The Visual Studio team similarly produces frequent updates for its development environment and online services. Clearly, there are teams within Microsoft that have adapted well to a world in which their applications are regularly updated.

Move beyond the world of on-premises software and into online and cloud services, and we see, both within Microsoft and beyond, increasing adoption of continuous delivery. Each update made to a system is automatically deployed onto production servers once it's passed sufficient automated testing.

It's true that none of these projects is as complicated at Windows. Ubuntu may contain a more diverse array of packages, but it benefits from many of these packages being developed as independent units anyway. Windows does, of course, contain many individual components, and Microsoft has done a lot of work to disentangle these. But the fact remains that its scale is unusually large—and unusually integrated. Windows is also, at least in places, extremely old.

These factors certainly make developing Windows challenging—but so challenging as to make two releases a year impractical? That's not clear at all. It just needs the right development process.

[contf] [contfnew]

Ars Technica

[contfnewc] [contfnewc]