Internet Relay Chat (IRC) turned 30 this August.

The venerable text-only chat system was first developed in 1988 by a Finnish computer scientist named Jarkko Oikarinen. Oikarinen couldn't have known at the time just how his creation would affect the lives of people around the world, but it became one of the key early tools that kept Ars Technica running as a virtual workplace—it even lead to love and marriage.

To honor IRC's 30th birthday, we're foregoing the cake and flowers in favor of some memories. Three long-time Ars staffers share some of their earliest IRC interactions, which remind us that the Internet has always been simultaneously wonderful and kind of terrible.

Lee Hutchinson, Senior technology editor

June 20, 1995 was the day I logged onto the Internet for the very first time.

It wasn't my first time being "online"—as a veteran of the 713 BBS scene, I was well acquainted with the world behind my modem—but "the Internet" was a thing about which I had only the vaguest of understandings. However, thanks to a NetCruiser account (handed out gratis by Netcom to Babbage's employees like me so that we'd be more likely to recommend the service to net-hungry customers), I found myself eagerly confronting the Internet of mid-1995. To my BBS-trained provincial self, it seemed almost impossibly vast.

NetCruiser was an all-in-one package that bundled together clients for email, telnet, finger, FTP, IRC, and the nascent World Wide Web into a single Windows application. It also came with its own dial-up TCP/IP stack, eliminating the need to screw around with Trumpet Winsock or its contemporaries. You simply typed in your NetCruiser account name and password and the application did the rest, dialing into the closest Netcom POP and handing you an IP address. It was kind of a middle ground between the walled gardens of AOL and CompuServe and the free-for-all of a direct university connection—there were some training wheels, but it was the actual-for-real Internet.

Clicking around on that long ago June afternoon, I found myself drawn to IRC. I had no idea what "Internet Relay Chat" was, but I assumed that I could talk to other people. Clicking NetCruiser's IRC button brought up a list of channels on EFNet (though this was before IRC's Great Split, and you could join other networks if desired), and that list was bewildering indeed.

But what to talk about? There were so many channels! Some were obvious (#sex seemed like it probably contained what it said on the tin), while some were inscrutable and lacked channel descriptions. One near the top of the list jumped out at me—#descent. I was a rabidly outspoken fan of Parallax's six-degrees-of-freedom space shooter, and the chance to chat with other Descent players seemed jaw-droppingly awesome. We could talk about strategy and tactics! We could talk about that damned level seven boss! Oh, this was going to be amazing!

Eagerly, I clicked and joined the channel. NetCruiser's IRC interface came up, with a layout similar to most graphical IRC clients—a participant list on the left, message window center, and a text entry field at the bottom. I typed my first words into the channel, anticipating that I would soon be talking to dozens of new friends.

There was a moment of silence, and then something odd happened. The channel went blank. The list of users disappeared, and NetCruiser politely played the Windows alert chime through the speakers. At the bottom of the IRC window, a new message now stood alone:

"You have been kicked from channel #descent for the following reason: fuck off newbie"

I guess the Internet of 1995 wasn't that different from the Internet of 2018.

Sam Machkovech, Tech culture editor

Some of my earliest IRC stories can be found in a feature-length story about my first girlfriend, who I met through IRC. But before romance bloomed in 1997, I spent the prior year just trying to get online—and then screwing with people's heads in adults-only chat rooms.

Yes: before I jumped into the world of blind online trust, of believing that another user was telling the truth about her age, gender, and location (A/S/L?!), I was passionate about blowing up other people's trust.

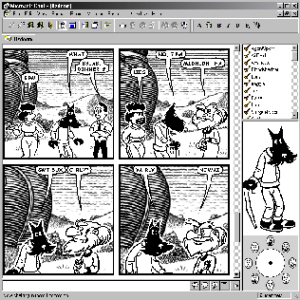

I don't tell this story with any sense of pride. Nor do I remember what compelled me to fake like a 22/F/Denver with some fetching handle. If my memory serves correctly, this was a reaction to the Microsoft-developed IRC client (Comic Chat) that came with my version of Windows 95 and featured a range of "sexy" cartoon avatars. Did people really use these?

For the uninitiated, Comic Chat turned plain-text chat rooms into black-and-white comic strips. Messages included metadata that the app would convert to specific visual cues (particularly "emotions" on the cartoon avatars' faces). The first general-interest chat rooms I landed in consistently suffered from a "swarm" syndrome, where any chatter who chose the voluptuous, crop-top-wearing character Anna would dominate the comic panels. Chatters would appear in the app's comic panels every time they were called out by name. Thus, any Anna users would appear over and over thanks to namechecks—and compliments about how the default cartoon looked.

Something about this tickled me, a high school loner with a superiority complex. "I'm so much better than these idiots," I probably said to myself while wearing a Throwing Copper T-shirt and cargo shorts my mom had bought for me. "I'll show them."

So, after a few anxious glances around my family's computer room, I'd log into channels like #adultsonly and #XXXchat, use the Anna avatar, and watch my "whisper" messages pile up. I typed whatever filthy stuff I could muster—gleaned from my older sister's advice-column magazines and my older brother's hidden box of skin mags, along with my own 15-year-old guesses about female anatomy. Like clockwork, I received typo-ridden messages about how hot I was.

That was the point at which I said I was ready to start a file transfer, so the chatter in question could see the lingerie in which I'd been typing. I grabbed a photo of an older, hairier guy from some GeoCities page, changed the file name, and hit send.

"There," I said to myself upon seeing the all-caps angry response land in my whisper channel. "I've changed the world today."

This wasn't some constant sociopathic practice. I did it only a few times, though I recall busting it out as a party trick if I was ever with a group of friends at an Internet-connected house. (I really only had one "impressive" skill at the time, a typing speed above 100 WPM, and this was clearly the best way to strut my nerdy peacock feathers.)

It's embarrassing to think back on this practice. But remembering it again now it convinced me that I could combine that teenaged assholery with years of technology writing and reporting to become a world-class phisher—should this Ars Technica thing not pan out.

I have Anna to thank for that misplaced confidence.

[contf] [contfnew]

Ars Technica

[contfnewc] [contfnewc]