Attackers from a group dubbed Poison Carp used one-click exploits and convincing social engineering to target iOS and Android phones belonging to Tibetan groups in a six-month campaign, researchers said. The attacks used mobile platforms to achieve a major escalation of the decade-long espionage hacks threatening the embattled religious community, researchers said.

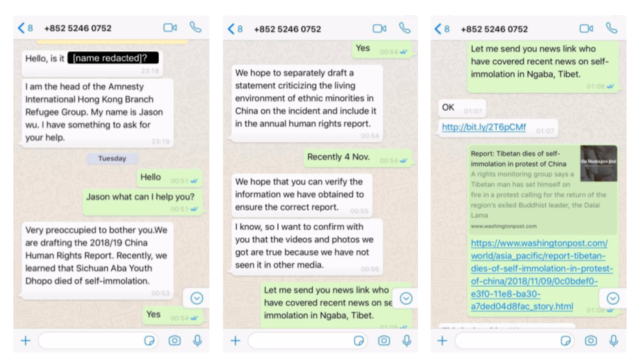

The report was published on Tuesday by Citizen Lab, a group at the University of Toronto's Munk School that researches hacks on activists, ethnic groups, and others. The report said the attackers posed as New York Times journalists, Amnesty International researchers, and others to engage in conversations over the WhatsApp messenger with individuals from the Private Office of His Holiness the Dalai Lama, the Central Tibetan Administration, the Tibetan Parliament, and Tibetan human rights groups. In the course of the conversation, the attackers would include links to websites that hosted "one-click" exploits—meaning they required only a single click to infect vulnerable phones.

Focused and persistent

None of the attacks Citizen Lab observed was successful, because the vulnerabilities exploited had already been patched on the iOS and Android devices that were attacked. Still, the attackers succeeded in getting eight of the 15 people they targeted to open malicious links, and bit.ly-shortened attack pages targeting iPhone users were clicked on 140 times. The research and coordination that went into bringing so many targeted people to the brink of exploitation suggest that the attackers behind the campaign—which ran from November 2018 to last May—were skilled and well organized.

In an email, Citizen Lab Research Fellow Bill Marczak wrote:

It was a focused and persistent attempt to compromise the mobile devices of senior members of the Tibetan community. Careful attention was made to the selection of targets and the social engineering. The operators created multiple fake personas and engaged targeted individuals in extensive conversations before sending exploit links. Overall, the ruse was persuasive: in eight of the 15 infection attempts, the targeted persons recall clicking the exploit link. Fortunately, all of these individuals were running non-vulnerable versions of iOS or Android, and were not infected.

The attacks observed by Citizen Lab overlap with those reported three weeks ago by Google Project Zero. The Project Zero post documented in-the-wild attacks exploiting 14 separate iOS vulnerabilities that were used over two years in an attempt to steal photos, emails, log-in credentials, and more from iPhones and iPads.

Researchers with security firm Volexity later reported finding 11 websites serving the interests of Uyghur Muslims that the researchers believed were tied to the attacks Project Zero identified. Those sites, Volexity said, targeted both iOS and Android phones.

Significant escalation

Tuesday's report said the same attackers used some of the same malware families—including iOS exploits that required only a single click to infect vulnerable phones—against individuals from Tibetan human groups.

"The campaign is the first documented case of one-click mobile exploits used to target Tibetan groups," Citizen Lab researchers wrote. "It represents a significant escalation in social engineering tactics and technical sophistication compared to what we typically have observed being used against the Tibetan community."

Of the 17 intrusion attempts Citizen Lab observed, 12 of them linked to pages hosting an attack chain that combined multiple iOS exploits. All but one of those links were sent over a three-day span in November, and the last one came on April 22. The exploit chain appeared to target iOS versions 11 through 11.4 on seven iPhone models ranging from 6 to X. It appears to correspond to this attack chain documented by Project Zero. By November, the vulnerabilities had already been patched for four months. All of the people targeted were running iPhones that had been patched, Citizen Lab said, and as a result, none of them were infected.

Exploits and encryption

While the exploits were delivered in the clear over HTTP connections, the exploits were also encrypted using an ECC Diffie-Hellman key exchange established by the targeted Web browser and the Poison Carp control server. The encryption would prevent any network intrusion detection systems from detecting malicious code. It would also make analysis of the attacks harder since analysts couldn't reconstruct the malicious code from a network traffic capture alone.

The iOS spyware payload the attackers tried to deliver was similar but not identical to the one from earlier this year described by Project Zero.

"Based on the technical details provided in the Google report, we believe the two implants represent the same spyware program in different stages of development," Citizen Lab researchers wrote. "The November 2018 version we obtained appears to represent a rudimentary stage of development: seemingly important methods that are unused, and the command and control (C2) implementation lacks even the most basic capabilities."

The implant analyzed by Project Zero, by contrast, provided a much fuller suite of capabilities.

The Android exploits, meanwhile, also failed to infect targets. Rather than develop the attacks on their own, Poison Carp members appear to have cribbed from proof-of-concept exploits posted by white hat researchers. One of the Poison Carp attacks used a working exploit published by security firm Exodus Intelligence for a Chrome browser bug that was fixed in source code—but the Exdous patch had not yet been distributed to Chrome users.

Other attacks included what appeared to be modified versions of Chrome exploit code published by two culprits. One appeared on the personal GitHub pages of a member of Tencent's Xuanwu Lab (tracked as CVE-2016-1646), who was also a member of Qihoo 360's Vulcan Team (CVE-2018-17480). The other came from a Google Project Zero member on the Chrome Bug Tracker (CVE-2018-6065).

Never-before-seen Android spyware

Unlike the iOS-based spyware, the spyware implant for Android was full featured and robust. The spyware was delivered in stages that started with "Moonshine," the name given to the implant's initial binary. To ensure that Moonshine achieves stealthy and rootless operation, it obtains persistence by overwriting a seldom-touched shared library that's used by one of the apps installed on an infected phone. When a target opens the app after being exploited, the app loads the maliciously modified library into memory. The code in later stages of the implant shows that the mechanism works with four apps—Facebook, Facebook Messenger, WeChat, and QQ—but the exploit site Citizen Lab analyzed only delivered exploits for the first two of those apps.