On Tuesday, polls will be open to voters in eight states, including California, which holds gubernatorial primaries among many other national, state, and local elections.

Under California law (Section 2194 of the Election Code), voter data (name, address, phone, age, party affiliation) is supposed to be "confidential and shall not appear on any computer terminal… or other medium routinely available to the public."

However, there's a big exception to that law: this data can be made available to political campaigns, including companies that provide digital analysis services to campaigns. In other words, candidates and their contractors can get voter data, but there's little definition in the law about how those parties are required to be custodians of that data and how that data ought to be secured.

"Campaigns are totally reckless with voter data—there's no question about it," said Kim Alexander, the president of the California Voter Foundation, a non-partisan organization that works on the logistics of voting in the Golden State.

It's worth noting that private voter data is often handled very cavalierly in many contests in the United States. In addition to recent controversies involving the Trump campaign, Cambridge Analytica, and others, there have been many large-scale breaches.

In 2015, for example, Georgia sent out physical CDs containing a slew of personal information for 6 million voters. Earlier this year, The Sacramento Bee inadvertently exposed voter data on more than 19.5 million California voters.

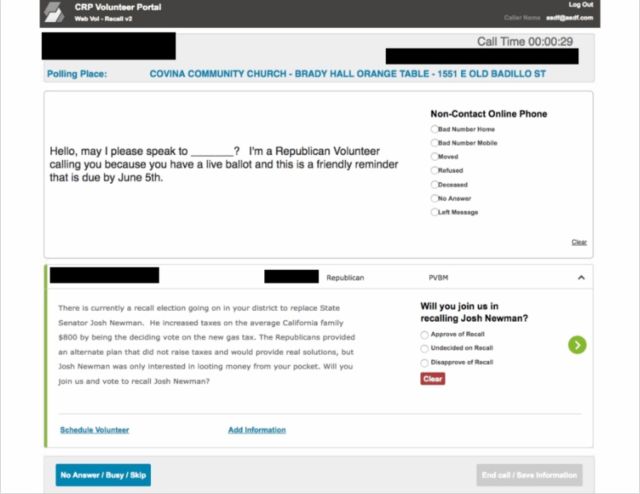

One much smaller example was made clear to Ars this week when we were sent a lengthy public URL (beginning with http://phonebank.the-pdi.com) designed for Republican volunteers in a Southern California recall campaign. The URL allowed us to access active Republican voter data, including names, addresses, phone numbers, ages, genders, and party affiliations.

We accessed this information without agreeing to any terms of use or stipulating that we were, in fact, Republican volunteers. The website had no meaningful security controls whatsoever.

Had we gone to the primary PDI login page first, we would have seen a click-through check box to a terms of use and a visible warning: "The Political Data Interface is only to be used for purposes that qualify as 'political' in accordance with the State of California privacy laws."

The Republican who shared this Web address with Ars did so out of concern that his party was lax when it comes to digital security. He told us that he would prefer a system in which, at a minimum, volunteers have to confirm an email address and not have such unfettered access to voter data that could be used by non-Republicans to cause mischief.

After we "signed up," we entered an obviously fake email address ("[email protected]") and provided a fake name in order to gain access to a volunteer portal. Once in, we could easily access the voter data, a few people at a time. (This information has been redacted in the image above.) Then, once we were done with our "call," a new set of voter information was generated and displayed.

The website did not even attempt to confirm our alleged email address. Rather, we were simply allowed to login with any made-up email address so long as we also entered a corresponding password. It's easy to imagine a scenario in which someone might attempt to scrape the website or perform other types of malicious social engineering on an unwitting voter.

Ira Rubinstein is an attorney and legal fellow at New York University who has written extensively on this issue. He told Ars that the free sharing of such voter data is not new, but it is troubling. "One would like to think that the volunteers had been identified or given some password," he said. "But it shows you there's very limited vetting of who's a volunteer."

When Ars explained this website to Kim Alexander of the California Voter Foundation, she was concerned. "To make it available online means that someone else could access it, and it's very sloppy, and it's not respectful to voters," Alexander said. "Voters are not a commodity; they are human beings. They should be treated with more respect than they are."

The Republican Party of California and its contractor, a Southern California firm named Political Data Inc., told Ars that this online tool is fully compliant with the laws that allow for sharing of voter data for political purposes.

"It's the way that campaigns are run," Paul Mitchell, a PDI vice president, told Ars. He also noted that his company had anti-scraping measures in place to prevent automated searches, but the company declined to specify what those measures are.

Mitchell compared such campaign tools to paper files of decades past and said that any campaign office would provide an online and/or texting method similar to this one as a way to reach out to voters. However, spiriting away large quantities of analog data that is not connected to the Internet would be far more difficult.

Plus, he said, volunteers don't typically share such data or use it for non-campaigning purposes.

"It's an honest, American thing to do, to phone bank, and ask them to support your candidate—this happens every day on every campaign," Mitchell continued. "There is no evidence that this was being abused, and if there was, they should have done something about it. That's how the process works."

Fabian Valdez, the California GOP's digital director, has given training sessions on PDI's software. He told Ars that there is nothing in this data that is "proprietary."

"So in terms of data security, one could see it as: 'I have access to all this voter data,' but it's not voter data that you couldn't get access to. There's no real concern on our end. If a Dem were to jump into our [volunteer] list, there's no concern that they're going to rip off our data, as they would have access to the same data."

Valdez added that he is unaware of "any abuse of this data."

[contf] [contfnew]

Ars Technica

[contfnewc] [contfnewc]