In the US, two types of electricity generation are on the rise: natural gas and renewables. If one of those is set to make a bigger mark than the other this year, it's natural gas: in 2018, natural gas-burning capacity is expected to outpace renewable capacity for the first time in five years, according to data from the Energy Information Agency.

All that additional natural gas capacity—approximately 21 GW expected this year—could spell trouble for the already-troubled coal and nuclear industries. Once a new gas facility is built, it makes it easier to close down older, inefficient coal plants, even if the price of natural gas rises a little. Coal plant closures have been happening for years already, and the Trump Administration has made a point of promising to bring coal back. But officials are having trouble finding a legal and politically acceptable way of boosting coal at the expense of natural gas, which is also a big US-based industry.

For nuclear, the problem is similar. The EIA wrote this week that the US nuclear energy industry is fighting not just against the falling cost of natural gas and renewable energy, also against the "limited growth in electric power demand."

Renewable numbers

Although natural gas additions are expected to overtake renewable energy additions in 2018, forecasts for renewable energy additions to the grid roughly match what we saw in 2017. Natural gas is overtaking renewables not because renewable energy adoption is slowing, but more because natural gas facilities are seeing a considerable boom.

In fact, barring any changes in the EIA numbers, natural gas, wind, and solar generation are the only electricity generation sources that will be added to the US grid in any consequential manner in 2018. Battery, hydroelectric, and biomass facilities make up the small percentage of "other" sources that are expected to come online this year.

Lots of natural gas capacity will be added to the PJM region, which is a central battleground in the tension between coal and natural gas. Energy Information Agency Comparing renewable and natural gas additions over the years Energy Information Administration

Renewable energy also started off the year strong. According to the EIA, "in February 2018, for the first time in decades, all of the new generating capacity coming online within a month were non-fossil-fueled. Of the 475 MW of capacity that came online in February, 81 percent was wind, 16 percent was solar photovoltaic, and the remaining 3 percent was hydro and biomass."

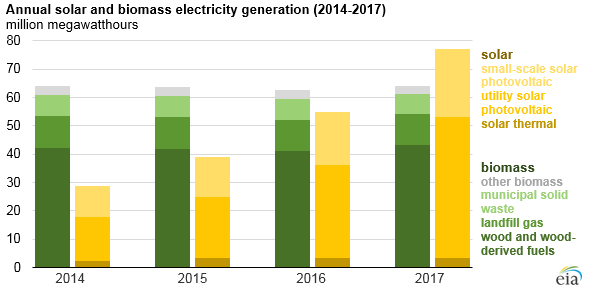

Solar has been building on its successes in the past year, possibly fueled in part by the threat of tariffs from the Trump Administration. In terms of energy generation, 2017 was the first year that solar passed biomass to become the third-most prevalent renewable energy in the US, after wind and hydroelectric power. "Electricity generation from solar resources in the United States reached 77 million megawatt hours (MWh) in 2017, surpassing for the first time annual generation from biomass resources, which generated 64 million MWh in 2017," the EIA wrote.

Nuclear outlook

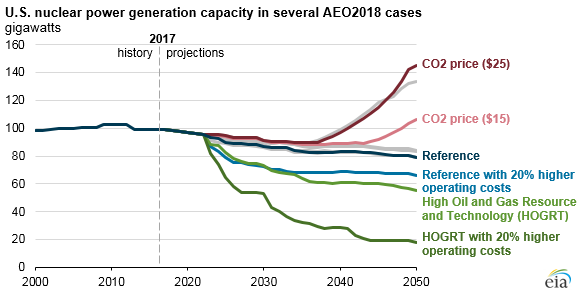

Finally, EIA took a look this week at the economic outlook for commercial nuclear electricity generation plants. The administration modeled several different projections for how capacity might change in the future, and its results suggest that, without a carbon tax, US nuclear capacity will likely fall over the next 30 years, in some cases dramatically.

Currently, 11 GW of the US' 99 GW of nuclear capacity is slated for retirement before 2025. Only the controversial expansion of the Vogtle nuclear power plant in Georgia, as well as some minor upgrades at existing plants, are expected to add capacity to the US nuclear fleet if all else is held equal.

If natural gas resources and technology expand dramatically over the next several years, the EIA projects that US nuclear capacity could fall to 55 GW by 2050 as nuclear facilities struggle to compete with cheap gas.

The EIA tested two cases in which carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions are subjected to fees of $15 per ton and $25 per ton. Since nuclear power emits no greenhouse gas during electricity production, such a tax would make nuclear energy competitive with natural gas and coal. In those situations, a $15 per ton fee would result in 106 GW of US nuclear capacity by 2050, and at $25 per ton, that number jumps to 145 GW by 2050.

[contf] [contfnew]

Ars Technica

[contfnewc] [contfnewc]