The Senate will have the first poke at Mark Zuckerberg later today, followed by the House Energy and Commerce Committee tomorrow.

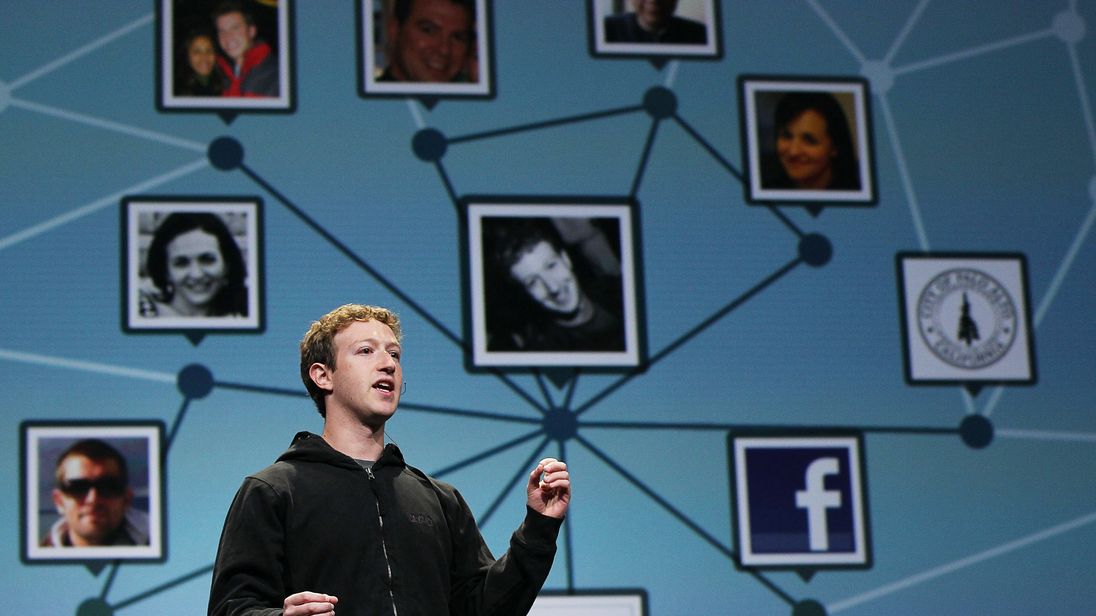

As Facebook's founder and CEO arrives on Capitol Hill to be quizzed by US lawmakers over a data breach hitting Facebook's users, it's ironic that it was a Facebook quiz that forced him to be summoned to Washington DC to answer questions of election interference, fake news, and privacy.

Sky News added three experts – Edward Lucas from The Centre for European Policy Analysis, Silkie Carlo from Big Brother Watch and Jamie Bartlett from the Centre for the Analysis of Social Media for Demos – to a group chat to find out the most pressing questions that need answering.

1. What has Facebook done since it was alerted to the mass-harvesting of user data in 2015?

The first reported incident of user accounts being exploited for political campaigning purposes was in 2015, when journalist Harry Davies was investigating early links between Cambridge Analytica and SCL Group.

He approached Facebook for comment, but was simply told "swift action" would be taken against anyone contravening their data policies.

2. How many of your users truly understand the amount of information that you collect on them, how you process it and how you monetise it?

For some, the idea that a Silicon Valley titan snoops on what you upload to their platform is not a surprise.

But, for many, Facebook has been their first interaction with the Internet, the only opportunity to keep in touch with friends and family and a standard port of call when logging on to any mobile device.

The rush to "like" pages dedicated to celebrities, films, music and more builds up a picture of your personality – the more you share about your personal history and interests, the more you let advertisers target you directly.

This makes Facebook an attractive business proposition compared to expensive, traditional media and allows the company to make money and build more services.

But for a network of 2.2 billion people across the world, it's not clear enough that their entire commercial model is about exploiting that personal information.

3. Will you make it easier to find out who's behind the advertising on Facebook?

Regulating online political advertising is a hot topic on the heels of alleged Russian interference.

Indeed, foreign powers spending money on social networks to influence elections seems like a low-cost high-benefit for those willing to do bad things to democracy.

A proposed verification of people buying the ads is only the first step – to truly embrace transparency, users should be able to find out why they're seeing an advert and the name of the purchaser running the campaign.

4. Would you be open to allowing academics access to data for research and regulatory purposes?

Some industries, like the airline industry, accept that a huge community of academic researchers, NGOs and other regulatory bodies should have access to data in spite of commercial concerns to ensure operational safety is its highest priority.

As social media is continually blamed for gang crime, extremism and a general erosion of public trust in politicians and news organisations, this access could kick-start a great contribution to cleaning up those problems.

5. How can you convince everyone that Facebook will change?

If the figurehead at the top refuses to step down, and the company's structure remains largely unaltered, a hiring spree of more moderators, verifiers and other behind-the-scenes teams will not be enough to stem growing scepticism.

The company remains beholden to a board of corporate shareholders and a trading price on the American stock exchange.

With its portfolio of companies – Instagram and its dedication to influencers and brands, WhatsApp's much-criticised (mainly by government ministers) instant messaging – and its future investment in AI-powered virtual assistants, the company is at a crossroads.

More from Facebook

It can no longer rely on PR-friendly public posts about "listening to our community" from its geek-chic CEO.

Mr Zuckerberg will need to commit to either reducing commercial revenue to prove he's serious about putting people before profit or admit that his original goal of "bringing the world closer together" relies on the long-accepted method of growing a business by increasing its earnings.

[contf] [contfnew]

Sky News

[contfnewc] [contfnewc]