Crawling along the worlds river bottoms, the larvae of the caddis fly suffer a perpetual housing crisis. To protect themselves from predators, they gather up sand grains and other sediment and paste them all together with silk, forming a cone that holds their worm-like bodies. As they mature and elongate, they have to continuously add material to the case—think of it like adding rooms to your home for the rest of your life, or at least until you turn into an adult insect. If the caddis fly larva somehow loses its case, its got to start from scratch, and thats quite the precarious situation for a defenseless tube of flesh. And now, the microplastic menace is piling onto the caddis flys list of tribulations.

Microplastic particles—pieces of plastic under 5 millimeters long—have already corrupted many of Earths environments, including the formerly pristine Arctic and deep-sea sediments. In a study published last year, researchers in Germany reported finding microplastic particles in the cases of caddis flies in the wild. Then, last month, they published the troubling results of lab experiments that found the more microplastic particles a caddis fly larva incorporates into its case, the weaker that structure becomes. That could open up caddis flies to greater predation, sending ripple effects through river ecosystems.

You may wonder why one insect species matters. But caddis flies are critical actors in these ecosystems, and their struggles could well have consequences. Caddis fly larvae work an important gig hoovering up aquatic vegetation, keeping a river from getting overgrown. As flying adults, they serve as a critical food source for bats, frogs, and spiders. This study is also helping open up a new front in microplastic science: Researchers have been massively ramping up their work to understand how ingested microplastic particles might affect the physiology and behavior of animals, but relatively little has been done to determine how those particles might affect the structures that insects like caddis flies, bees, and termites build.

The researchers used two kinds of plastic in this new experiment, polyvinyl chloride, which you know as PVC, and polyethylene terephthalate, or PET, a clear plastic used to make plastic bottles. In the lab, they chopped up the plastics into tiny pieces, which they mixed with sand in various concentrations. Then they let the caddis fly larvae do their thing.

The researchers found that the larvae used both kinds of microplastic to build their cases, especially in the early stages of construction. “We think that's because maybe the plastic is lighter, so it's not as hard to lift,” says biologist Sonja Ehlers of the German Federal Institute of Hydrology, lead author on the paper in the journal Environmental Science and Pollution Research. “And so the larvae start using those lighter materials instead of just choosing sand grains.”

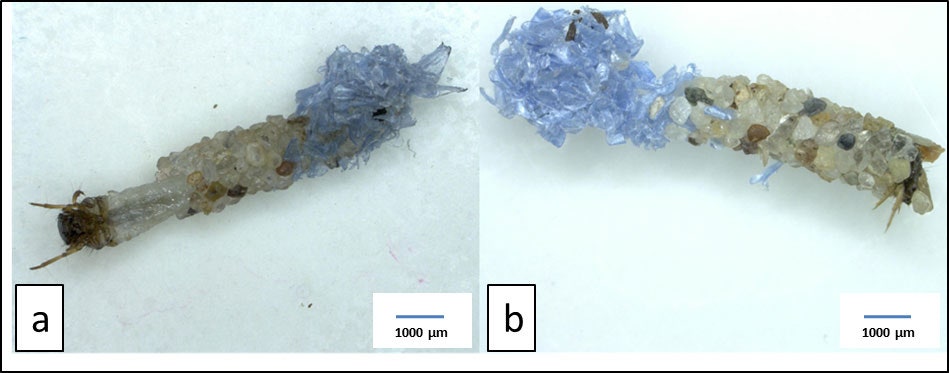

Indeed, if you take a look at the image above, you can see the far end of the case is nearly all blue plastic. That was the part the larva built first. As the larva grew bigger, it was able to heft bigger and heavier natural grains, which is why the bits of the case closest to its head are sandier.

Now, take a look at this image of the silk holding the particles together. “In cases where there was plastic, the silk there had more holes, and it was not as firm,” Ehlers says. In addition, “plastic is a softer material than sand, and it's also lighter. And so this might be a reason why if there's more plastic and less sand in the case, then it collapses more easily.” Ehlers and her colleagues quantified this with a device that measures how much force is required to crush each case.

Thats not good, for the obvious reason that the caddis fly larva relies on the structural integrity of its case to protect itself from predatory fish. And its potentially not good for more subtle reasons: The case helps camouflage the larva on the river bottom. That may not be a problem if the sediment the case is lying in is also littered with the same microplastics the insect used to build its protective outer layer; it will still blend in. But caddis flies often move around a river ecosystem, so if one ends up in an area less contaminated with microplastics, or even more contaminated with them, its technicolored case could make it stick out. Increased predation could in turn affect the ecosystem as a whole, if the larvae arent able to do their work cleaning up vegetation.

Being in such close contact with microplastic could cause physiological problems for the larva, as these materials are known to emit toxins known as leachates. “They also use the case for respiration,” Ehlers says. “They are creating water flow inside the case so the water passes their gills. And so if there's plastic incorporated, then of course those leachates could also reach the gills maybe and do some harm.”

A more long-term concern, for the caddis fly larvae and any number of other organisms at the base of food chains, is bioaccumulation. A small fish eats a larva, a bigger fish eats the smaller fish, all the way on up, and the concentrations of microplastic and associated toxins accumulate over time. The bigger predators that people eat, like tuna, may be absorbing those microplastics and the chemicals they leach. We still Read More – Source

[contf] [contfnew]

arstechnica

[contfnewc] [contfnewc]