Look, we're admittedly biased around the Ars Orbital HQ. Whether the best of times or worst of times, we routinely find comfort in a good book. COVID-19 has changed so much about our day-to-day lives, including some of our entertainment habits around things like gaming or streaming TV and film. But when it comes to precious reading time in between work and busy personal lives, we're continually drawn to the stories that grip us—as grim as some of those may be.

This year's staff summer recommendation/To Be Read list has a few newer releases, plenty of old classics, and a lot of alternate reality/sci-fi. Ars' book tastes remain nothing if not on-brand, meaning we may never get through one of these without Douglas Adams being mentioned. Here's everything, Hitchhiker's Guides and others, we've been escaping to.

Series starters

Sci-fi fans who enjoy engaging characters and story driven more by human interaction than technical wharrgarbl will enjoy John Scalzi's latest trilogy, The Interdependency. The third book just released last week, and it ties things up neatly—a first, for Scalzi. The Interdependency is an old-school galaxy-spanning empire, with a twist—habitable planets are almost impossibly difficult to find, and in an effort to curtail war, the Interdependency was designed so that no system can survive without trade with the others.

This arrangement is fine, until systems begin being inexorably—and permanently—cutting off from access to one another, heralding a collapse of civilization itself. Scalzi lightly channels the kind of wry humor the late, great Douglas Adams was best known for, though never going over-the-top into outright comedy.

If you're looking for something a little further off the beaten path, I've also been enjoying a series called The Murderbot Diaries, by Martha Wells. I'm only a couple of books into the five-book series, but Wells' description of a confused rogue AI in a cyborg body, with absolutely everything designed, maintained, and forcibly supplied by the lowest bidder, is both charming and engaging. The Murderbot has its own desires, needs, and goals—it's just not too clear what those are, beyond doing as half-assed a job as possible in order to leave more time for trashy soap-opera consumption.

—Jim Salter, Technology Reporter

Sci-fi, lots of sci-fi

I read, um, kind of a lot—between 50 and 100 novels a year, most years—and I'm always happy to talk books. In these quarantimes, leaning in and running away seem to be the two big categories in my reading. Sticking to books that were published in the last decade (so leaving out annual comfort re-reads of Lloyd Alexander and Terry Pratchett), I have some thoughts.

If you like motley crews in space: Becky Chambers's Wayfarer series, starting with The Long Way to a Small, Angry Planet. Chambers's books are optimistic, character-driven science fiction; stories about people and how they feel in a strange and exciting future. Soft and cozy reading.

Just this week I also finished the two books to date in Alex White's Salvagers series, starting with A Big Ship at the Edge of the Universe. Motley crew of talented space pirates, but also with magic and a set of moral codes. Zippy reading, genuine fun.

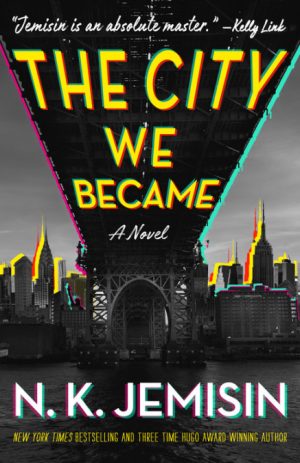

If you like cities: I cannot recommend N.K. Jemisin's latest, The City We Became, highly enough, especially if you love cities and double especially if you've spent any time in New York. I haven't lived in New York City since 2008, and I still could smell and feel and hear every single page. Cities have souls, and this is their story.

If you liked Hidden Figures: Mary Robinette Kowal's Lady Astronaut books, The Calculating Stars and The Fated Sky. As a Washington, DC, resident, I didn't love my home being wiped off the map at the start of the apocalypse, but for all that a story of doom kicks off the tale, it is optimistic, Right Stuff spacefaring fiction at its finest.

And if you really want to lean into the apocalypse: Chuck Wendig's Wanderers poses a pandemic from an animal-borne virus striking humanity right against the landscape of a US presidential election year. It's the wrong book to read in our actual 2020 if you're prone to giving yourself nightmares, but it's still a very good book.

—Kate Cox, Tech Policy Reporter

Two greats set in the past

Now is the perfect time to read Lovecraft Country, the 2016 dark fantasy/horror novel by Matt Ruff, since HBO's adapted series will debut in August. Set in the Jim Crow era of the 1950s, it's structured almost as a series of short stories, although everything is inter-related and hangs together beautifully as a whole. The first quarter focuses on Atticus, a black Korean war veteran and big H.P. Lovecraft fan, despite the author's notorious racism. When his estranged father disappears, leaving a cryptic message, Atticus sets out on a road trip from Chicago's South Side to rural Massachusetts. He's accompanied by his Uncle George—publisher of The Safe Negro Travel Guide—and his childhood friend Letitia.

There are plenty of sly references to the works of Lovecraft for the astute reader, as we encounter a secret cabal called the Order of the Ancient Dawn, a haunted house, a strange pocket universe, time shifting, shape-shifters, an evil mannequin, and a cursed book. What makes the book so ingeniously subversive, however, is that the worst monsters are not eldritch terrors or a Shoggoth in the woods; it's the stark racism and bigotry our protagonists encounter along the way.

Beyond that, I've got one other recommendation: Iain Pears' sprawling 1997 novel, An Instance of the Fingerpost. Part historical murder mystery, part philosophical rumination on the unreliability of human memory and personal narratives—aka the "Rashomon effect" after Akira Kurosawa's classic 1950 film— the novel remains one of my all-time favorite reads that I return to every few years. The title refers to a quote from Francis Bacon, who held that all evidence is fallible, and yet there can be "one instance of a fingerpost that points in one direction only, and allows of no other possibility."

Pears is a former BBC reporter who garnered early success with his art-history mysteries featuring fictional detective/art historian Jonathan Argyll. Those novels are light and quite fun, but with Fingerpost, Pears attains a whole new level of thematic complexity. It's almost as if he started out writing a simple tale of a 17th-century Oxford murder, only to be carried away as that world and its denizens came alive for him. It's been justly compared to Umberto Eco's 1980 bestselling novel The Name of the Rose, although I prefer Fingerpost.

This was a tumultuous period of enlightenment, when new scientific ideas were flourishing and conflicting with religious institutions, and political intrigue was everywhere. There are four sections, each narrated by a different character, each remembering their version of the 1663 arsenic poisoning of a man named Robert Grove many years later. A servant girl confessed, but the four witnesses—an Italian physician, the son of an alleged Royalist traitor, a cryptographer, and an Oxford archivist—each identified a different culprit, and only one will ultimately reveal the truth about what really happened. Pears masterfully evokes Restoration England, as Charles II regained the throne after Oliver Cromwell's short-lived attempt at a republic, and his characters (historical figures and fictional ones) are richly detailed. It's a long book but so riveting that you'll be tempted to devour it as fast as possible, and you'll be pondering the nature of truth entirely by the end.

—Jennifer Ouellette, Senior Writer

Modern classics

My suggestions might cut a little close to the bone for some, but hey, we each deal with the slow-burning apocalypse in our own way. Which is why my first recommendation is Margaret Atwood's MaddAdam trilogy, starting with the excellent Oryx and Crake. Set some years in the future, it's the story of the end of the world against a backdrop of plausible biotechnology. Atwood is more famous for The Handmaid's Tale, but Oryx and Crake definitely struck a nerve with this one-time scientist.

Second up is a pair of books from William Gibson, The Peripheral and his latest, Agency. These deal with time travel, but not really in the way you're used to. In the 22nd century, someone—it's never said who—worked out how to send information back in time. That creates a new timeline, called a stub, and in the 22nd century, some people are manipulating or exploiting stubs for their own amusement. If Atwood's books describe the apocalypse and its immediate aftermath, Gibson sets his stories in the decades before, and the decades after, with references here and there to "the jackpot," which wasn't just one thing, but the weight of all the horrible things we know are happening around us, from environmental degradation and climate change to pandemics made worse by political and social incompetence.

Finally, there's the old standby of Douglas Adams' Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy. I read it as a precocious child but enjoy it even more now I get all the jokes. It's probably best to stop reading after So Long and Thanks for All the Fish, because Adams was depressed when he wrote Mostly Harmless, and it's a way more nihilistic book than anything involving the end of the world.

—Jonathan Gitlin, Automotive Editor

It's a handsome book jacket, but it also has the most literary nuggets since Haruki Murakami's running journal. Nathan Mattise Read More – Source [contf] [contfnew]

arstechnica

[contfnewc] [contfnewc]