Earlier this year, several amateur astronomers spotted an unusual anomaly on the planet Jupiter: bits of the gas giant's famed Great Red Spot appeared to be flaking off, raising fears that the planet's most identifiable feature might be showing signs of disappearing. But Philip Marcus, a physicist at the University of California, Berkeley, begs to differ. He argues that reports of the red spot's death have been greatly exaggerated, and at a meeting of the American Physical Society's Division of Fluid Dynamics in Seattle this week, he offered an intriguing counter-explanation for the flaking.

The Great Red Spot is basically a gigantic storm in Jupiter's atmosphere, about 22 degrees south of the planet's equator. Because it's located in the southern hemisphere, it rotates counter-clockwise, meaning it's more of an "anti-cyclone." The 17th-century scientist Robert Hooke is commonly credited with the first recorded observation of the red spot in 1664, although some contend Giovanni Cassini provided a more convincing description in 1665. After 1713, there were no reported observations for over 100 years, until the red spot was observed again in 1830 and continually thereafter. Despite the gap in recorded observations, many astronomers believe it's the same storm, still going strong more than 350 years later.

This isn't the first time an alarm has been raised about the possible dissolution of the red spot. Back in 2004, astronomers concluded that it was shrinking, compared to 100 years ago, and the spot seems to have been shrinking even more rapidly since 2012. In May 2017, the Gemini North telescope on the summit of Hawaii's Maunakea captured an image of a small hook-like cloud on the red spot's western side, as well as a long wave, or "streamer," extending off its eastern side.

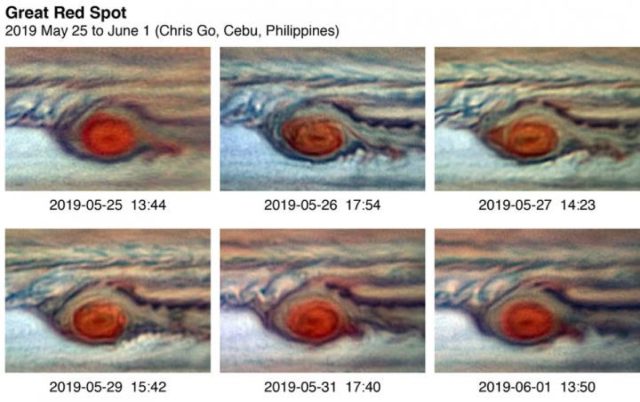

Earlier this year, the Juno spacecraft photographed large red "flakes" breaking off from the Great Red Spot. Then, on May 19, 2019, an Australian amateur astronomer named Anthony Wesley captured an image of a streamer peeling away from the red spot; he spotted the same phenomenon on May 22. Similar observations by amateur astronomers followed, variously described as "hooks" and "blades," as well as flakes and streamers.

"Each streamer appears to disconnect from the Great Red Spot and dissipate," Wesley told EarthSky. "Then, after about a week, a new streamer forms and the process repeats. You have to be lucky to catch it happening; Jupiter spins on its axis every 10 hours and the Great Red Spot is not always visible."

According to Prof. Marcus, however, his computer models demonstrate that the flaking is not a death knell for the Great Red Spot at all. Rather, it's a very natural weather phenomenon arising from the complex fluid dynamics of Jupiter's atmosphere. During a press conference, he cited two specific factors that he thinks are responsible for the flaking observed earlier this year.

First, there are mergers, because an anti-cyclone like the red spot will attract other anti-cyclones while repelling regular cyclones in the atmosphere. "It's the opposite of electrical charges," he said. "Opposite charges attract and like charges repel each other." But on Jupiter, like attracts like (anti-cyclones to anti-cyclones) and oppositesRead More – Source