It's not that “We need that truck” and “Find a gun" are unusual orders to be given in a video game. Certainly not in a Call of Duty video game. The series has always impelled players forward with extended drills of Sergeant Simon Says (“Man that mortar!” “Plant those charges!” “Take out that sniper!”). So normally, I would hop to it reflexively. Ive called in airstrikes and breached into rooms of uncounted hostiles just because some grizzled green beret barked at me. Its not that.

Game Details

Developer: Activision and Infinity Ward

Platforms: Xbox One, PlayStation4, PC

Release Date: Oct. 25, 2019

Price: $60

ESRB Rating: M for Mature, 17+

Links: Amazon | Official website

What strikes me when playing the new Call of Duty: Modern Warfare is that the directives are coming from someone whos 10 years old, tops. Hes telling his sister (no older) to go kill a couple Russian soldiers and steal their truck.

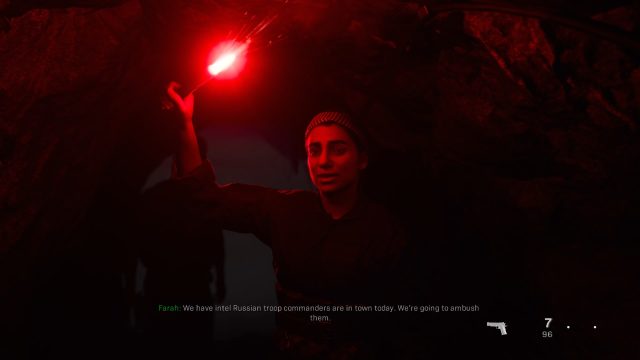

Im already familiar with these two as adults in the present, where theyre Hadir and Farah, ultracompetent freedom fighters for the nation of Urzikstan. But this is a flashback to what Im to understand is their first brush with war, when occupying Russian forces gas their village and kill their father.

Mind you, that doesnt stop them from sneaking through the chlorine fog in gas masks, past troops firing perfunctory bullets into the dead or dying. Its a gutsy performance. They dont flinch at the gunshots—in fact, theyve already killed one soldier by then. As Farah, I stalked that soldier from cover and stabbed at him precisely three times, the fatal number for most video game bosses (Hadir, encouragingly after one thrust: “Its working!”). At the edge of town, Hadir stops near a transport guarded by two soldiers: “If we run away, theyll catch us.”

Then, with composure befitting a tier one operator. “We need that truck,” I'm told. “Find a gun.”

Out of the mouths of relative babies, objectives are updated. The gun is graciously signposted—its on top of a covered well in the center of the scene. Hadir wants me to call his cell phone to distract the soldiers, grab the revolver, ice them, and steal the truck.

The sequence has the kind of logic that I imagine might appeal to a video game character. But I find that when I shoot one of the guards, the other immediately spots me in the tall grass: Game Over. I fail this routine a couple times before a solution occurs to me: I angle Farah up an incline to line up both guards heads behind the handguns sights, press L3 to steady her aim, and drop both with a single bullet.

Neither tween acknowledges the double headshot. But the game does: I get an achievement named “Two Birds.”

Double action

Released in late October, Call of Duty: Modern Warfare is filled with scenes and sequences that repackage the horrors of war in a distinctly video-gamey package. To put it plainly, this edition should be familiar to series veterans.

In the multiplayer mode of 2009s Modern Warfare 2, for instance, killing two people with one bullet earned you a prog rock riff and an achievement titled "Collateral Damage.” Its both a plaudit for one of the miniature feats of dexterity players can pull off and a fun little nod to civilian war deaths.

Ive known a double-kill is a thing you can do with guns in games for at least that long. Its one of the many factoids in my minds “gun basket,” as Kirk Hamilton would put it, alongside the relative merits of red dot and holographic sights. Same goes for where the magazine is located on a bullpup.

On the subject of storage, this rebooted Modern Warfare continues Call of Dutys tradition of partitioning itself into three discrete modes: campaign, competitive multiplayer, and cooperative multiplayer. These distinctions have been an aid to our own tendency as players to compartmentalize things, too. The campaigns bring the clearest authorial intent, but usually these stories clock in at a tidy five-to-seven hours. Theyre often viewed as an amuse bouche of wartime gravitas before the competitive multiplayer entrée, where mass murder becomes the swaggering killstreak, and collateral damage gets you new banner art for your player card.

Infinity Ward design their campaigns in such a way that a well-versed competitive player wont feel inhibited. Both modes run at the same heart-stopping pace, and skills translate between them one-to-one. So does the arsenal, now more foregrounded than ever, replete with weapon modeling modes that take the games metaphorical status as a showroom for gun manufacturers and makes it literal. Want to know if a rifle features a “slow cycle rate” or “a short stroke piston system?" Modern Warfare expects that you do, and it may well be right.

Modern Warfare does reintroduce some friction into the series patented feedback loop. Its multiplayer stages are rats nests of back alleys and sneaky sight lines that bog down the flow of movement. I prefer it to the lane-style maps of previous games. It keeps me in the moment, attuned to my surroundings instead of sprinting around to make big, looping attacks on enemy flanks. The guns, which were starting to take on an interchangeable point-and-click precision over the years, now tend to have more dramatically different recoil profiles.

But these changes can hardly rein in a decades worth of evolution in the name of slick, hypersynaptic ergonomy. The speed of Call of Duty, the sensation of being a free camera mounted on a gun, is unchanged, whether youre playing as a hardened SAS operative or a Middle Eastern child.

Perhaps thats why the most effective moments in the campaign are the scenes just preceding that flashback moment, when Farah is trapped under the ruins of a bombed building and cant move at all. White Helmets pull her from the rubble and deliver her to her father's arms, and from there she can only witness the scenes of ensuing destruction in whirling glimpses.

Because as soon as shes boots-on-the-ground again, she will be comfortably back in Call of Dutys generous possibility space for e-athletes, where even a child who's never held a gun can steady her aim to within a pixel's breadth.

That multiplayer, tho

Theres an urgency to Modern Warfares campaign thats come undone from any in-fiction justifications. Im barely told who Ill be shooting at or why before the game jams my hands full of C4 to plant, molotovs to lob, and remote controlled bombs to pilot. Its a lot. I have the sensation being harried forward, forward… like some kind of Light Brigade cavalryman being ordered on into the fun, “theirs not to make reply, theirs not to reason why.”

Multiplayer neatly solves that problem by nuking any context from orbit. Call of Duty doesnt even name its factions “Opposing Force” anymore, let alone “Terrorists,” as Counterstrike does. Here its “Coalition” versus “Allegiance,” variegated patchworks of nations and military-types, a proxy of proxy wars. They bomb and snipe across a changing series of maps and modes, like the new Battlefield-style large-scale “Ground War,” or the compact 2v2 series, “Gunfight.”

The game benefits, in a small but noteworthy way, from one successful attempt to capture the horror of war: the soundscape. Rich with booms, pings, and chattering fire, the audio environment plays devilishly with the rattle and spark of the visual environment, sending you ducking and whirling and thinking every explosion and whistle of a bullet was meant for you.

And the levels themselves, now dense with detail, have made it more difficult to pick out targets from the surroundings, rewarding patience and punishing carelessness. But fidelity (visual or otherwise) will only benefit these games if it can force them to slow down all the way to the point where players dont rack up body counts in the high hundreds—where the violence is forced to be fully considered, instead of just providing a new sheen for realistic weapons of war.

When it was revealed that Modern Warfare would include white phosphorous as a killstreak reward, there was a smattering of outcry. White phosphorous stands out for its gruesomeness, and for its prolonged, scarring effects, even as it resides in a gray area of international law.

Certainly there was already nothing humane about the gunships and bombing runs that populate the killstreak catalogue. But the inclusion of white phosphorous is glaring because until now, white phosphorus has had no effective PR. While spec operatives and .50 cal rifles, and even AC-130 gunships, have been treated to kind mentions in recent media, not many storytellers have been willing to cast the horrors of white phosphorous in a positive light.

But the US has likely used white phosphorus in attacks, and so it must be due for image rehabilitation. Games can play an outsized PR role in this, and this attempt to sublimate white phosphorous into that pantheon must be seen as part of that effort. It should bother us, even if weve already accepted so much.

Listing image by Activision and Infinity Ward

Pathos for pyros

How do you tell a story about the horrors of war to players whove been trained up in your own virtual proving grounds? Players who can kill eight men with a cinder block? And how do you do it without alienating potential markets (and the Department of Defense)?

Perhaps you start by drawing lines in the sand. One line forms the borders of a fictional nation, Urzikstan, a mish-mash of Syria, Libya, Afghanistan et alia—it's a county seemingly contrived for plausible deniability. Its the home of Farah and Hadir, but also Al-Qatala, a bald-faced Al-Qaeda stand-in. The game draws another line around the use of chemical weapons (Farah, owing to her past, particularly despises them), a shipment of which you show go missing from a Russian-occupied Urzikstan base.

And then you start crossing those lines, systematically. Al-Qatala stages a massive terrorist attack in Londons Piccadilly Circus, prompting a Western military response. In a parallel plot, Russia cracks down on the locals in retaliation for the theft of the chemical weapons. Only, its technically not Russia: its the rogue forces of Russian General Barkov. Video games tend to like these Kurtzian figures, who can antagonize the player on a person-to-person level and provide an effigy that can be beaten satisfactorily (unlike, say, the whole military industrial complex). Theyre characters who can wield a nations army and yet be said to be atypical of it.

So when Farah observes of CIA operative Alex, “So you do kill Russians,” the reply can come: “Only the bad ones.” It seems to be Barkov's fictional force that the game, in a much criticized move, holds responsible for the real American war crimes at the "Highway of Death." Notably, real Russians seem a tad skeptical of these artistic liberties.

I am Trash Man

Here is a list of some of the things that General Barkov says if you listen all the way through his broadcast looping in the level “Embedded.”

“These insurgents continue to launch senseless attacks in the name of so-called “freedom.”

“There can be no order and no peace until those who side with these savages are permanently eliminated.”

“There will be no judge and no jury, only crime and punishment.”

“My reserves of manpower are inexhaustible.”

“We can make an example of those who refuse.”

“These enemies are your friends and families.”

“I am a fair man, and a man of swift judgement.”

“Embedded” is one of those "Pirates of the Caribbean but for war crimes" theme park-style tours video games are wont to do. Soldiers hold barking dogs just back from forced laborers. Bodies hang from makeshift gallows. Theres a soldier who will continue beating a civilian in a looping animation until you get bored and shuffle on, dutifully crossing some invisible tripwire that triggers the scream and the gunshot that will cut it short. Schlocky propaganda posters with Barkov in front of various slogans are plastered on the walls, and his message drones over the loudspeakers to hammer home the connection between villain and misdeed.

Barkovs antagonistic relationship to Farah is one of the storys main through-lines. As Kotaku reports, in earlier builds it was charged with more sexual menace, but notably, even in the released version Barkov smiles and inexplicably purrs “perfect” as he captures Farah and Hadir. And when, in a later scene, he waterboards an adolescent Farah, Barkov bizarrely “coaches” the player through their own virtual torture. The minigame awkwardly merges latent paternalism with the crudely gamelike instructions to rotate the joystick to avoid the pouring water.

Throughout, Barkov alternates between taunts and cries of “How are you doing this!?” As representations of torture go, it feels less like “the very definition of human evil” than it does cringeworthy melodrama.

The Person Closet

“Good guys look like bad guys around here. Shits fucked up.” – Unnamed marine, Modern Warfare

Torture presents a lot of practical problems as a video game device, even when its not so clumsily executed. Principally, the problem is that the player is not actually being tortured—theyre not, in fact, experiencing anything even remotely evocative of the sensation of being tortured. The sheer, somatic extremity of such a scene throws the player back out of the body of their avatar and onto their couch. Pain in a video game only makes it through as friction: a vibration in the controller, or a smear of blood across the screen blocking the view. Fear of death runs into the obvious “extra life” problem.

Surprise, on the other hand, works great. So does the fear that comes from being chased, or fear of the dark. And so thats what video games do. They bring zombie hordes to swarm after the player without sense of self-preservation, or bash against the outer side of windows. They place creatures behind doors and blind corners, ready to burst forth suddenly or scurry just out of range of a flashlights beam.

Modern Warfare does these things, too, but it does them with humans. It does the whole "flashlight" bit in its very first mission, a taut firefight with a few Russian soldiers. Later, it borrows from 2013s République for a segment where you remotely guide a civilian through a scene of violence, using security cameras for vantage.

Strikingly, several battles have a preamble, in which the protagonists chatter worriedly about whether men milling nearby are militia plotting an attack or whether cars approaching hold bombs. But the attacks always do come eventually, and when they do, its always hundreds of Al-Qatala fighters. They rush from the dark at the heroes positions on high, and they have to be illuminated with flares to see and kill. In other scenes, such as a nighttime raid on a terrorist cell in a walk-up, enemies spring out from doors and side rooms to attack.

I do not know enough to speak to the realism of these scenes. I only know that they look and feel like things that Ive done before in many video games that were not purporting to portray the realities of modern warfare. That alone makes me skeptical of the games claimed reality and the fears its trading on.

“At the end of the day, someone has to make the enemy scared of the dark,” says Captain Price, the squads leader and one of the games moral compasses. But theRead More – Source