Pop musicians have spent centuries flirting with technology to push the boundaries of the art, from the Theremin to mid-century tape experiments. Despite this fascination, only a tiny niche have gone so far as to programmatically generate music via code. In a span of roughly 70 years, the few whove done so comprise a Venn diagram of intersecting programmers and avant-garde musicians.

The results are unlike anything you've ever heard—and some of the most ambitious music to blend the realms of analog and digital sound.

I talked with people who are using code to make a wide variety of music, from sample mangling to a live algorithmic radio show to preaching the Marxist qualities of open source software. Despite the technological complexity and deep algebra involved, they are all seeking something very simple: a creative sandbox unbound by conventions of time and theory.

"A way of thinking suggested by the program"

Carl Stone has been mangling samples (“mangle” being an agreed-upon verb among sound manipulators) since 1973. He borrows them from commercial music, tears them apart, and glues them back together in nonsensical ways, with results resembling everything from a pop song played backwards to rapid gunfire made from a human voice. So, it was no surprise to me when I discovered (after a sonic onslaught of a February 2020 show where elderly people plugged their ears) that he exclusively uses Max, a beloved programming language for music and multimedia. Its a visual workspace with musical commands presented as modular boxes that you can chain with virtual wires. The open-ended design allows for free-flowing experimentation.

“You start each coding experience with a completely blank slate,” Stone says. “Its unlike any of the other commercial programs that have preconceptions and optimizations built in. A program like [Ableton] Live—which I respect very much—tends toward a way of thinking thats suggested by the program itself.”

Without that framework, Stones compositions are overtly surreal. He likens his sample-based work to an anagram: “It has a semblance of semantic meaning, but its strange.”

A Los Angeles native and CalArts graduate with little coding background, the 67-year-old has been making music on computers since 1986. He worked with '80s algorithmic music software such as Jam Factory and Laurie Spiegels influential Music Mouse. He describes his 80s computers as “luggable” for the road, and he toured with a Macintosh Plus for years.

Don't copy that floppy?

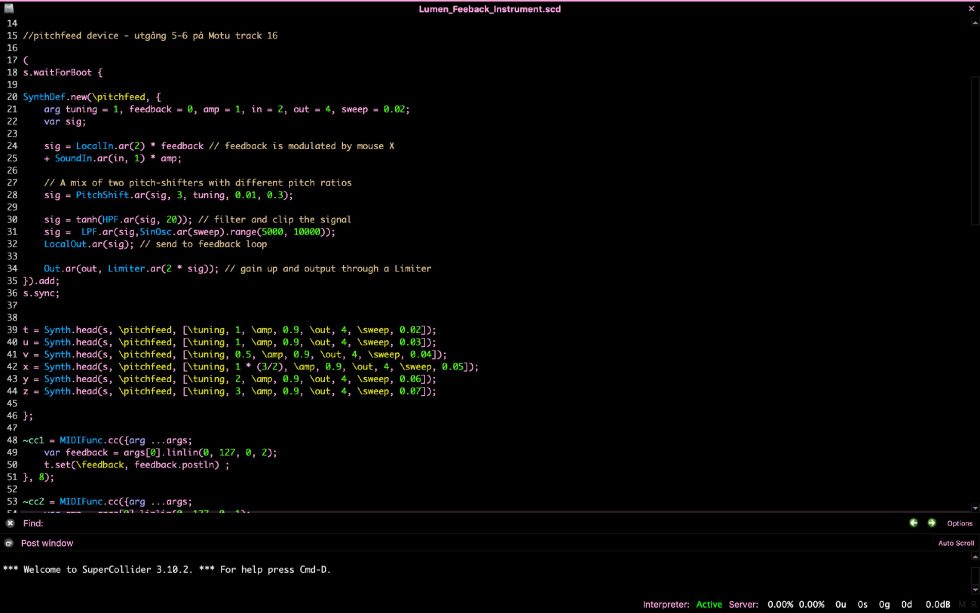

Carl Stone, performing live in the early 1990s with an Apple Macintosh SE/30. Ed Colver Carl Stone's typical on-screen arrangement of a Max patch. As he describes it via email: "The photo is of a performance setup of indium modules with specific functions (e.g. load a buffer and cut it up, perform an FFT function, play a sound file, take an external input, mix, etc.)." Carl Stone

Stone discovered Max (named after computer music pioneer Max Mathews) in 1989 during an artist residency in Japan, when his friend slipped him a pirated version on a floppy disk. At this point, Max could only send out MIDI info and couldnt handle signal processing. Stone began performing with it, frequently collaborating with Japanese video artists, dancers, and musicians.

Hes witnessed the software transform over the years: Signal processing and visual processing were later incorporated. The software got hackey-sacked between different corporations, with Stone formally beta testing its development at various stages. Eventually, one of its developers founded a company to sell it, Cycling '74. An outside party used Max to breadboard the wildly popular music software Ableton Live. The two programs eventually integrated, and soon after, Ableton absorbed Cycling 74 altogether.

Predictably, Stone has resisted the linear temptations of Ableton integration, and his recent output is more radical than his work from 30 years ago (one of his newer songs sounds a lot like the electronic subgenre vaporwave, but he says he has never heard of such a concept). He performs with an iPad and laptop, wearing a felt hat and using OSC (Open Sound Control) to send control data to his Max patches. Hes lived in Japan full-time since 2001, teaching at Chukyo University; hes spent his quarantine in Los Angeles, though, teaching Zoom classes to Japanese students at 2am local time.

His newest album, Stolen Car (an anagram of his name), was released on September 25.

"The code is the piece"

While Stone works with a commercial visual programming product, programmatic-music scenes in Berlin, Oslo, and Stockholm have embraced open sourced, text-based language. One hub is Stockholms XKatedral label. Co-founder Maria W. Horn, employee Daniel Karlsson, and artist David Granström video-called me at 4am my time from their shared studio. They showed me their “black metal” antique organ and the view of Mälaren, the third-largest freshwater lake in Sweden.

All three make electroacoustic drone music, reminiscent of experimental artists and bands such as Tim Hecker, Sunn O))), and Taylor Deupree. (If I may be so bold: It's the kind of music perfect for getting lost on Swedish tundra.) They use the language SuperCollider, which was released in 1996 and has been thriving as an open source project since 2002. They perform live via MIDI controllers, although Granström went through a purist “the code is the piece” phase where he would merely stand next to his laptop and let the patch run.

When they began coding at the Royal College of Music in Stockholm, Horn and Karlsson found the language exceedingly difficult until they began using Patterns, one of the five paradigms of SuperCollider. It runs on stateless, declarative phrases, which allows for a quicker, more natural form of expression. Granström also uses Patterns, but, being the so-called genius of the group, he had no problem grasping it.

"The fact that SuperCollider is free was a big deal for me," Horn says. "If youre new to musical programming, its a big step to buy a program like Max. I loved the fact that there was already a community in place where you can learn from each other.” In a back-and-forth on the topic, Karlsson rattles off what the duo means by "free"—"Open source, libre free, Stallman free.” And when Horn describes the "subversive" quality of open source programs, Karlsson adds, "I want everyone to have access to anything. I want freedom of expression for everyone. Im a Marxist.”

Horn interrupts this with a single word—"Cult"—while Karlsson doubles down on his egalitarian aspirations for the "open source movement" in art. Fittingly, Horns recent project Kontrapoetik features an experimental yet social justice-minded meditation on Swedish workers movements, witchcraft trials, and feminist reinterpretations of Satanism. The trios most recent projects can be found here, here, and here.

24 hours of randomness

Unlike the musicians mentioned above, Philadelphia-based William Fields has never played a “real” instrument. (The Swedes played in metal bands, while Stones jug band recently had a 55-year reunion.) Fields, in fact, made an instrument of his own.

The 42-year-old was always into computers, from his first Commodore 64 to the corporate IT jobs in his adult life. In the 90s, he used DAWs (Digital Audio Workstations—think something like Ableton), painstakingly drawing in all the notes by hand. After having kids and forfeiting his free time, he turned to improvisational music. First he was modulating his friends live music with additional audio effects. Then he kept developing more features until he created an entire performance system of his own, not currently available for public use.

His setup runs on a laptop using REAPER for its audio, utilizing REAPERs own JSFX language. Its controlled with an iPad running his custom user interface designed with the app Lemur. He calls his system FieldsOS. With a self-made UI, he says, “you can develop muscle memory and get really good at playing your own instrument.”

The true fun began when he made a button that randomized every parameter. “Randomization helps me explore this musical possibility space and find interesting places that I normally wouldnt mind,” Fields says. “Otherwise I would make 4/4 rhythms with a snare on the second and fourth beat.” [Editor's note: Ars Technica has previously covered experimental music with a built-in random-effects button.]

He began tuning the qualities of the randomness to make it sound less awful, which led to what he calls "genre" buttons: “First, I made a techno button. It would constrain certain things—for example, always being a 4/4 steady bass drum.”

Soon he was automating it with JavaScript. FieldsOS moderated itself, hitting its own reset button every 30 seconds. “It was like a slot machine,” he says. He pitched this concept to Resonance Extra, an experimental British radio block. He got a slot and dedicated each hour-long broadcast of his show to a different genre button, coding a new one each week and broadcasting it with no edits. These genres included Footwork, Wonky, and UK Garage, along with made-up genres like “Brownian Techno'' (in which the song slowly falls apart) and “Breeding Music” (in which compositions “reproduce” with one another). Eventually, he started to run out of genres, so he released the full 24-hour archive as an album on Bandcamp and called it a day. The massive $24 album oozes a futuristic gloss that sounds like it is accelerating into eternity.

Fields is currently seeking an app developer to help him make FieldsOS into a commercially marketable product. His new album, Read More – Source

[contf] [contfnew]

arstechnica

[contfnewc] [contfnewc]