Teasing out the myriad influences on any artist creating a timeless masterpiece is tricky business, but Finnish director Dome Karukoski does an admirable job of it in Tolkien, an evocative dramatization of the late linguistics professor and beloved fantasy author's early life.

Per the film's official premise: "As a child, J.R.R. Tolkien becomes friends with a group of fellow artists and writers at his school, with whom he finds inspiration and courage. Their bond of fellowship grows with the years, as they experience life together. Meanwhile, Tolkien meets Edith Bratt, with whom he falls in love. But when World War I breaks out, Tolkien's relationships with his friends are tested, an act which threatens to tear their "fellowship" apart." Nicholas Hoult (The Favourite) heads the cast in the title role, with Lily Collins (Okja) playing Edith.

The broad strokes of those formative years provide the backbone of the film. In 1892, John Ronald Reuel Tolkien was born in modern-day South Africa while his bank manager father, Arthur, had left England to manage a branch of the British bank there. When Tolkien was three, his mother, Mabel, took him and his younger brother, Hilary, for an extended trip to England. His father was meant to join them but died of rheumatic fever, leaving the family with no source of income. Mabel and the children wound up living in Birmingham with her parents, and the nearby village of Sarehole would end up inspiring various scenes in Tolkien's novels.

Mabel died when Tolkien was 12, and a local priest, Father Francis Xavier Morgan, assumed guardianship of Tolkien and his brother and ensured they received a good education. It was at King Edward's School that Tolkien met Rob Gilson, Geoffrey Bache Smith, and Christopher Wiseman, forming their own artistic society: the Tea Club and Barrovian Society, or T.C.B.S. That brotherhood anchors the film, which follows the young, idealistic dreamers who wanted to change the world with their art as they march off to defend Great Britain in World War I.

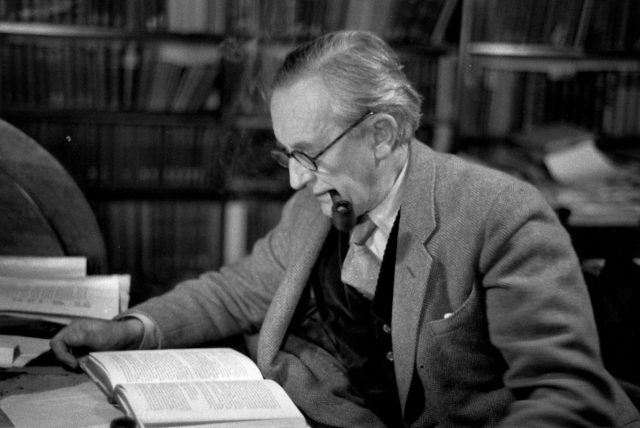

Later (after the events of the film), Tolkien bonded over a shared love of Norse mythology with Narnia-creator C.S. Lewis when the two men met at Oxford as professors in the 1930s. Along with several other Oxford-based writers and scholars, they began meeting regularly at a local pub called The Eagle and Child, fondly dubbed The Bird and the Baby. The Oxford Inklings, as they came to be called, were arguably the literary mythmakers of the mid-20th century, at least in England. That is the period of Tolkien's life most familiar to fans of The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings trilogy. In fact, Lewis was the first to read early drafts of Tolkiens imagined world. Tolkien later credited Lewis with "an unpayable debt" for convincing him the "stuff" could be more than a "private hobby."

But most of us are less familiar with Tolkien's formative years. "To me it was surprising, as I always envisioned Tolkien like everyone else: with his pipe at The Eagle and Child, debating with C.S. Lewis about elves," said Karukoski. "Then I found out he had all this background, being an orphan, finding his friends, going to war. The story is quite amazing." So Karukoski set out to bring it to life on film.

“For me, what is most important is to find the emotional truth of the character.”

Making a film about such a well-known and beloved literary figure is always a daunting prospect, especially in light of the sometimes litigious Tolkien Estate. The Estate did release a statement in April clarifying that the family "did not approve of, authorize, or participate in the making of this film" and "they do not endorse it or its content in any way." But a spokesman for the estate told The Guardian that statement wasn't a harbinger of legal action. The intent was simply to distance the Tolkien Estate from Tolkien the film, lest people confuse the director's artistic vision with historical fact.

Karukoski isn't bothered at all by the statement, which he thought was "quite respectful. I didn't feel offended." In fact, he has invited Tolkien family members view the film with him, with the hope they'll see he has treated their forebear with great respect. That said, he readily admits to taking some creative license with the facts of Tolkien's life in his interpretation of the author as a character.

"Almost any biopic or real-life story needs alterations, because everyday existence is not that exciting or cinematic. At the end of the day, the narrative flow must work," he said. "For me, what is most important [for a biopic] is to find the emotional truth of the character."

Still, there are many factual flourishes throughout. Tolkien really did fall in love with a fellow boarder, Edith, only to be forced to choose between her and an Oxford education, thanks to Father Francis (played by Miles O'Brien himself, Colm Meaney). A scene in a Birmingham teahouse where the couple toss lumps of sugar into the hats of fancy diners is largely accurate (except the real Tolkien and Edith sat on a balcony and tossed the lumps into the hats of passersby below). Edith was briefly engaged to someone else but broke it off when Tolkien declared he still loved her. They married after the war ended. And the tragic fates of two T.C.B.S. members are also part of the historical record.

Image from forthcoming film Tolkien. YouTube/Fox Searchlight Image from forthcoming film Tolkien. YouTube/Fox Searchlight Image from forthcoming film Tolkien. YouTube/Fox Searchlight Image from forthcoming film Tolkien. YouTube/Fox Searchlight Image from forthcoming film Tolkien. YouTube/Fox Searchlight Image from forthcoming film Tolkien. YouTube/Fox Searchlight Image from forthcoming film Tolkien. YouTube/Fox Searchlight Image from forthcoming film Tolkien. YouTube/Fox Searchlight Image from forthcoming film Tolkien. Read More – Source [contf] [contfnew]

Ars Technica

[contfnewc] [contfnewc]